Jorge Eduardo Eielson (Lima, 1921–Milan, 2006) drew no distinctions as he moved between the realm of the image and the realm of the word. Though he formed part of a modernist generation of postwar Peruvian painters inspired by the ancestral past, his art—produced as an exile by volition in Europe—quickly settled on an experimental tone informed by his interest in writing. Be that as it may, Eielson always tried to avoid the restrictions of set categories and genres, as he made clear in an interview with Peruvian writer Julio Ramón Ribeyro:

“[…] I have written articles for newspapers, and I am not a journalist. I have written plays, and I am not a playwright. I also make sculptures without being a sculptor. I have written short stories, and I am not a storyteller. A novel and a half, and I am not a novelist. In 1962, I composed a solemn mass for magnetic tape in honor of Marilyn Monroe, and recently I have been working on a concert, and I am not a musician. As you can see, I’m not anything.” [1]

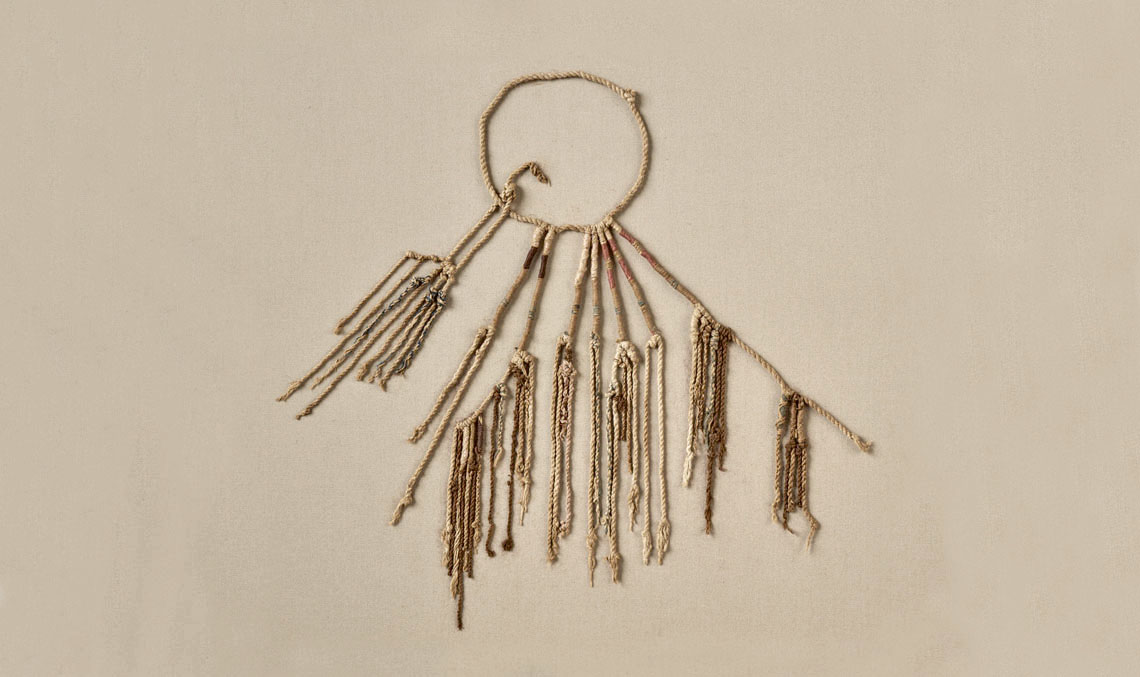

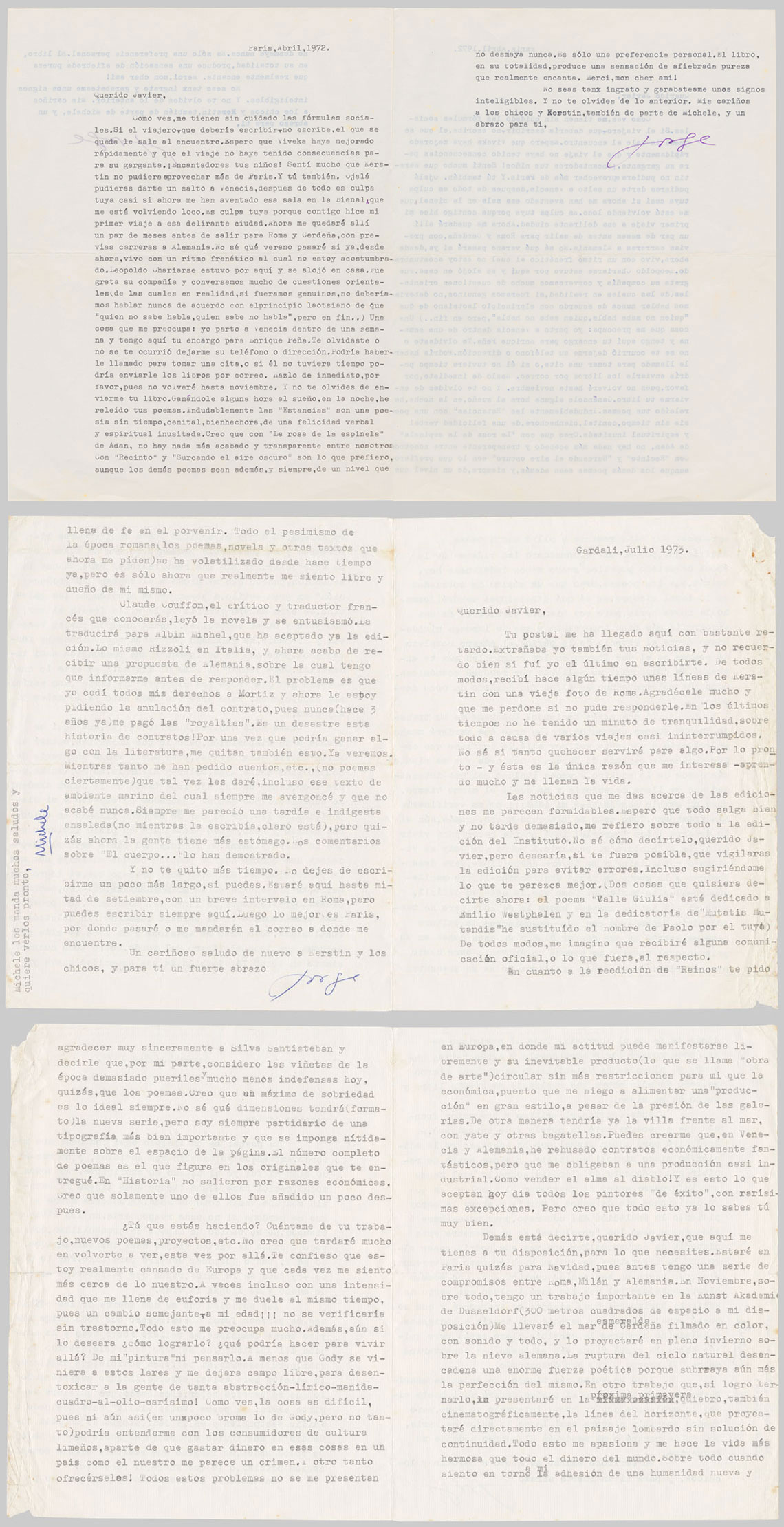

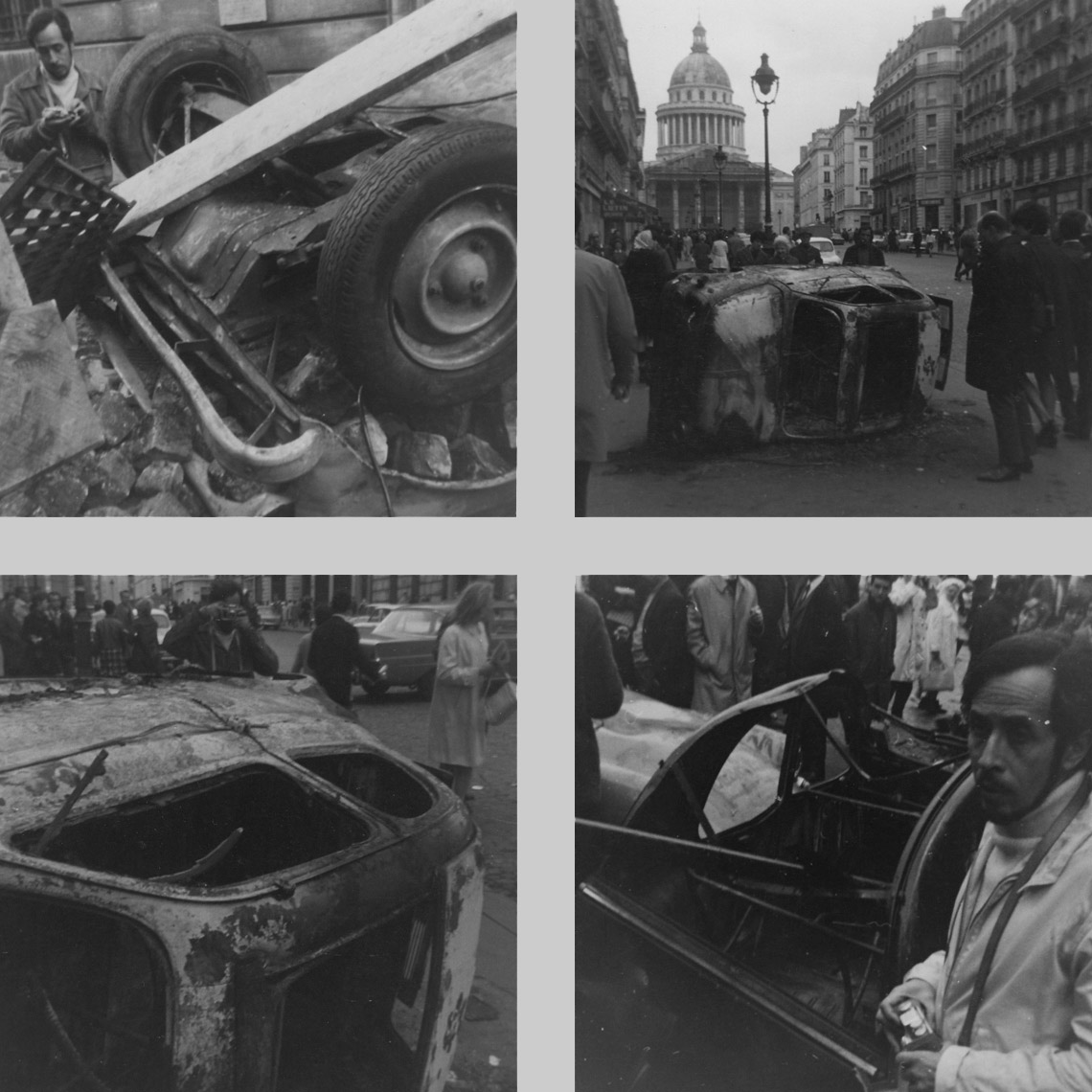

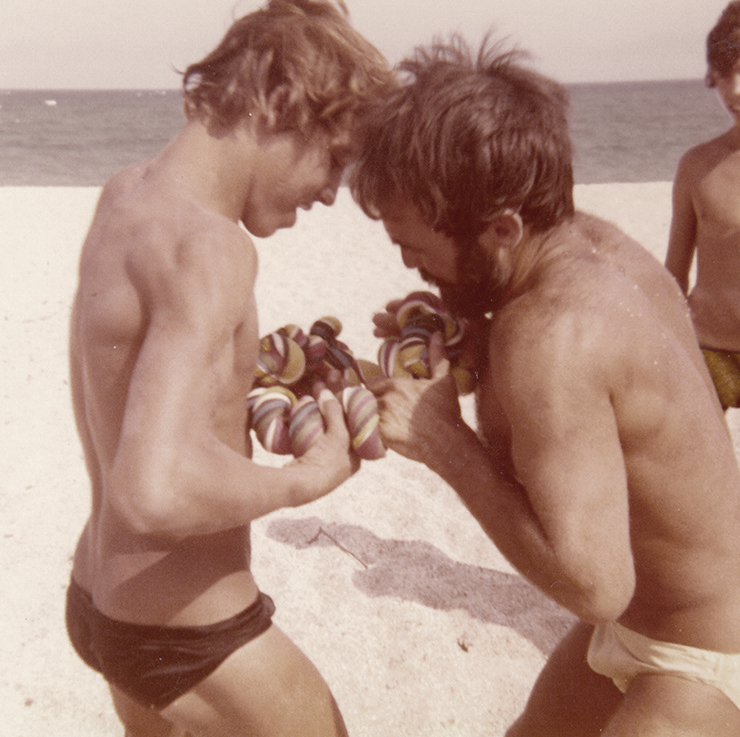

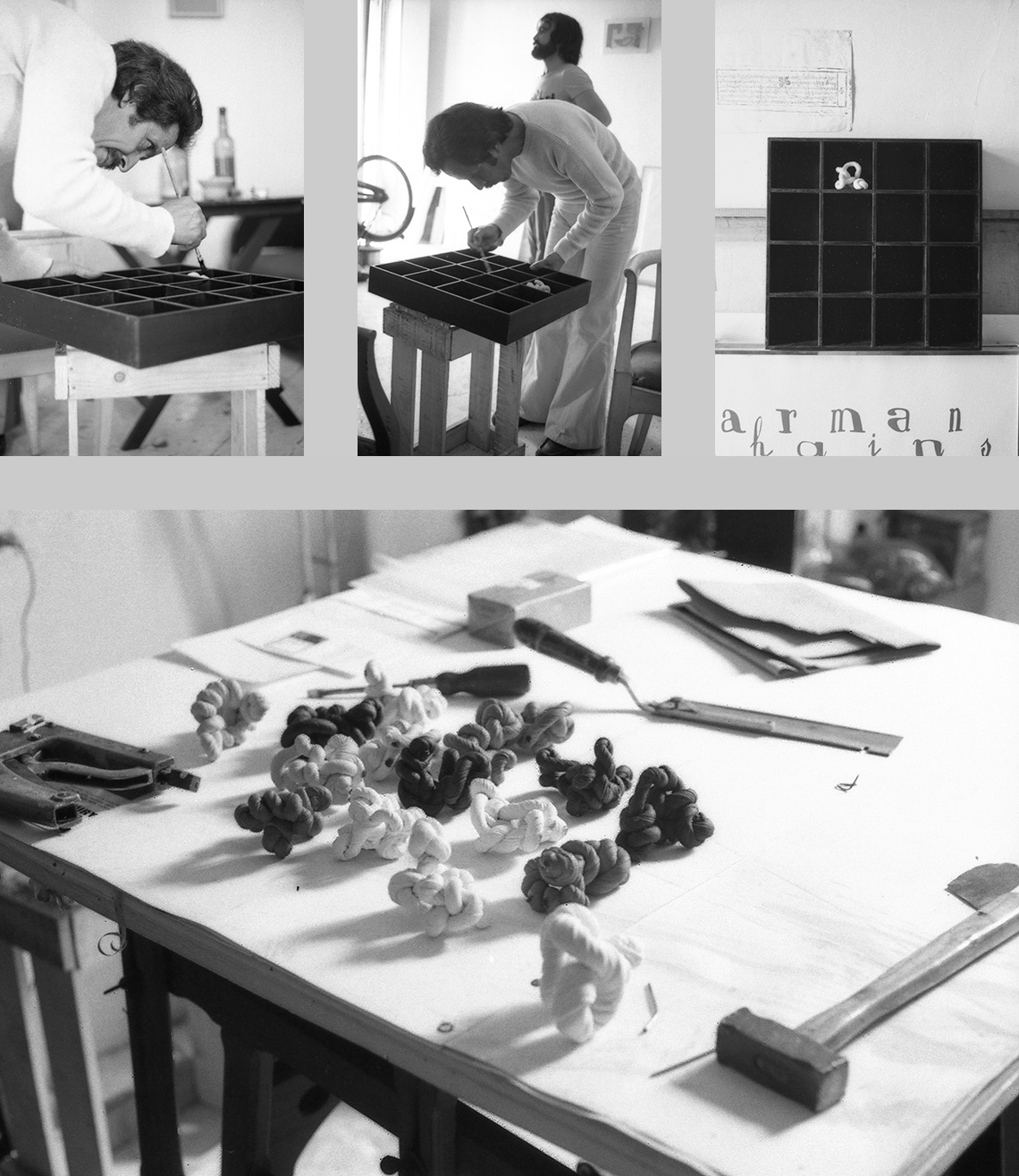

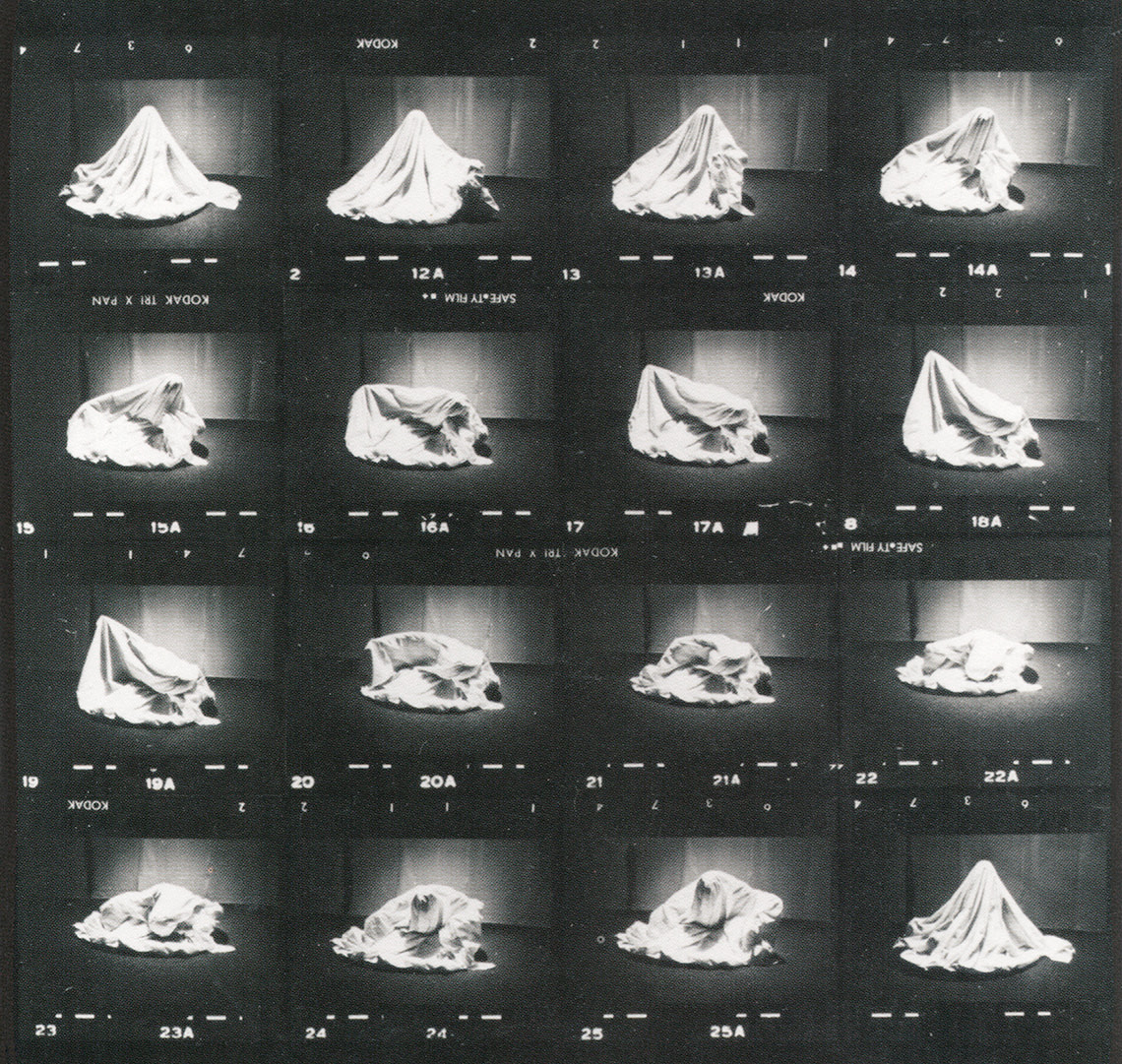

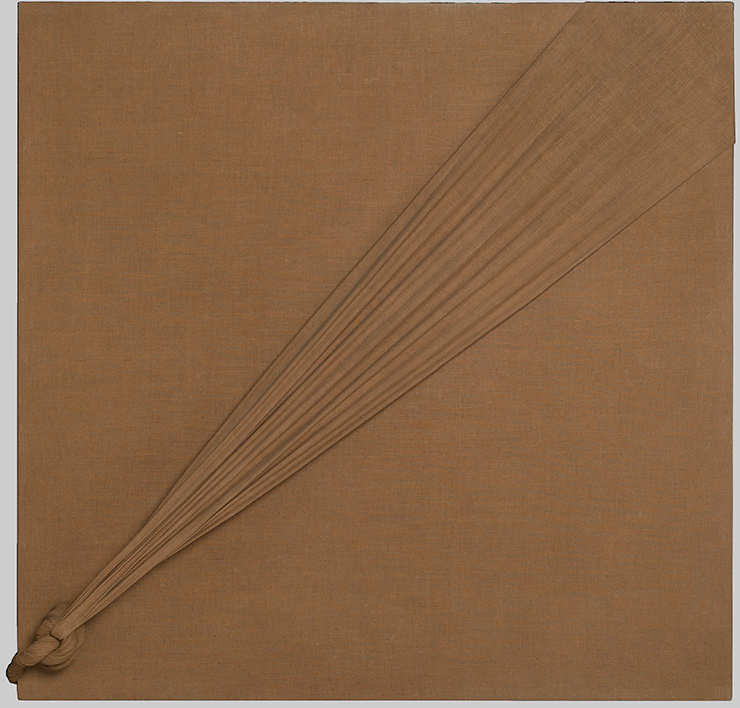

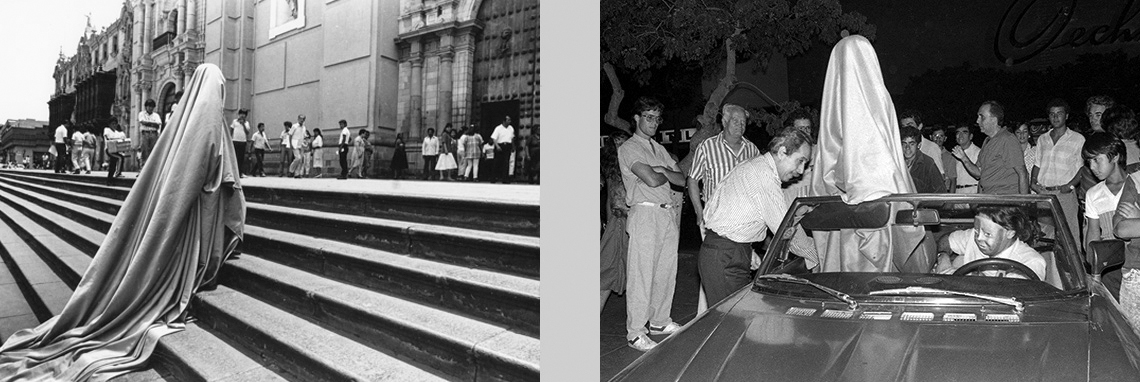

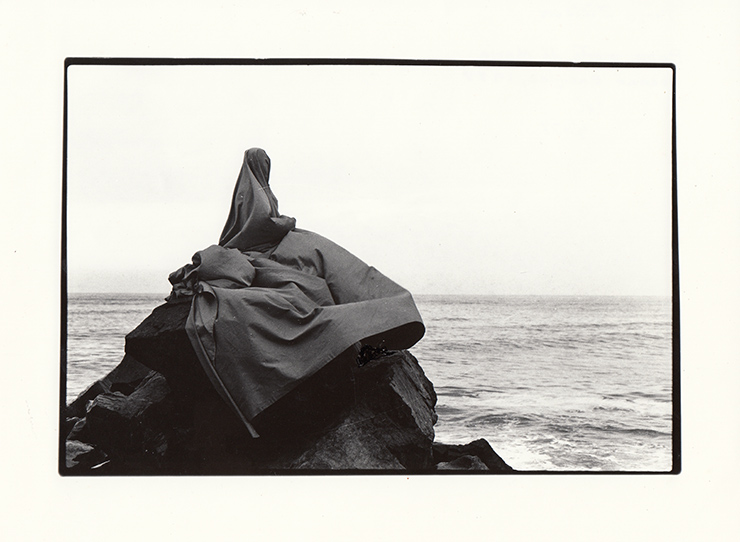

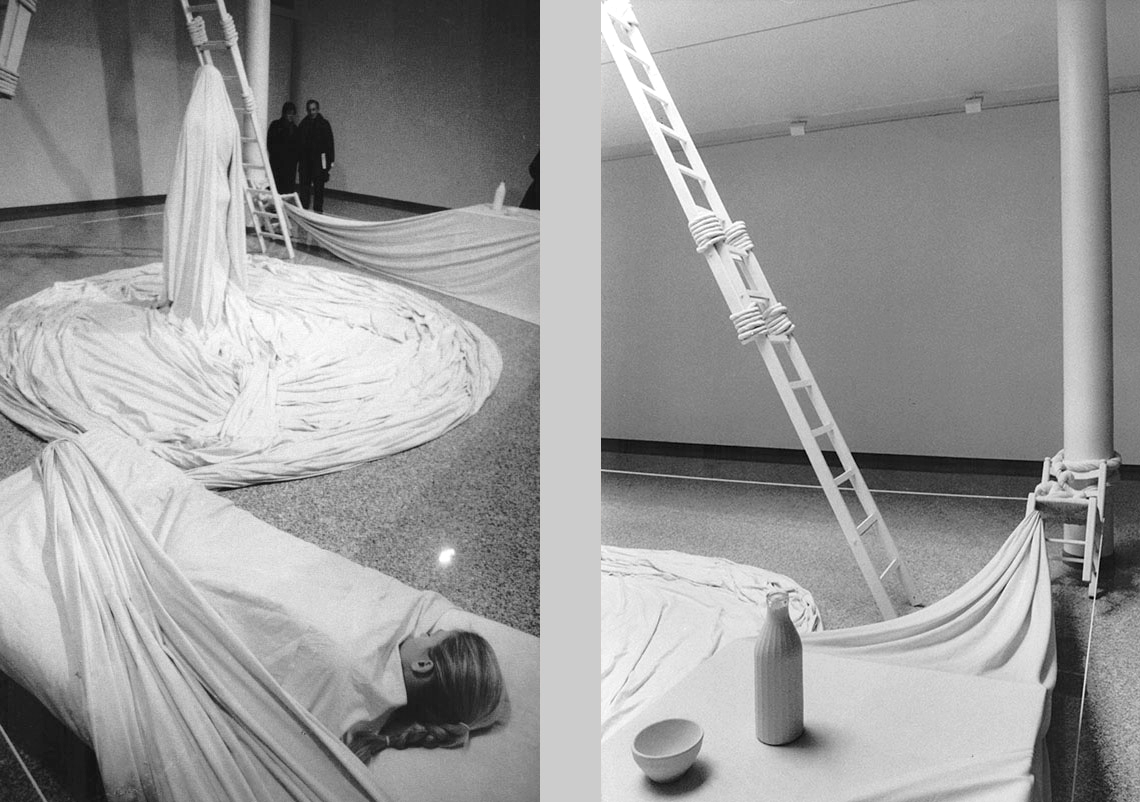

Eielson’s art is unquestionably tied to the sustained interest on the part of twentieth-century Latin American artists—from Joaquín Torres García and Xul Solar to César Paternosto, to name just one possible line—in connecting abstraction and Native American peoples. [2] While he forms part of that lineage, Eielson is the first of those twentieth-century artists to work with quipus, or knots, that draw inspiration from pre-Columbian cultures. Produced starting in the early nineteen-sixties, that groundbreaking body of work takes the shape of clusters of knots, tensions, and twists in the canvas over the stretcher—abstract constructive elements with chromatic codification organized as a series. In the late nineteen-sixties, Eielson’s quipus took on a sculptural dimension as they jutted out into space as installations. Twists in the canvas would be one of the foundations for performances like El Cuerpo de Giulia-no [The Body of Giulia-No] presented at the 1972 Venice Biennale. Though Eielson’s pictorial system is nominally tied to the bookkeeping system used by the inhabitants of ancient Peru, his variations configure a language that slips away from narrative, anecdote, or historical theme. He is not satisfied to simply reference ancient Andean civilization; he does not fall into nationalist traps. In Eielson’s art, the pre-Columbian is inserted into the present. In the case of the quipus, that insertion is effected by creating a notation system, a system of signs that builds a linguistic bridge over the gap between the pre-Hispanic world and modernity. [3]

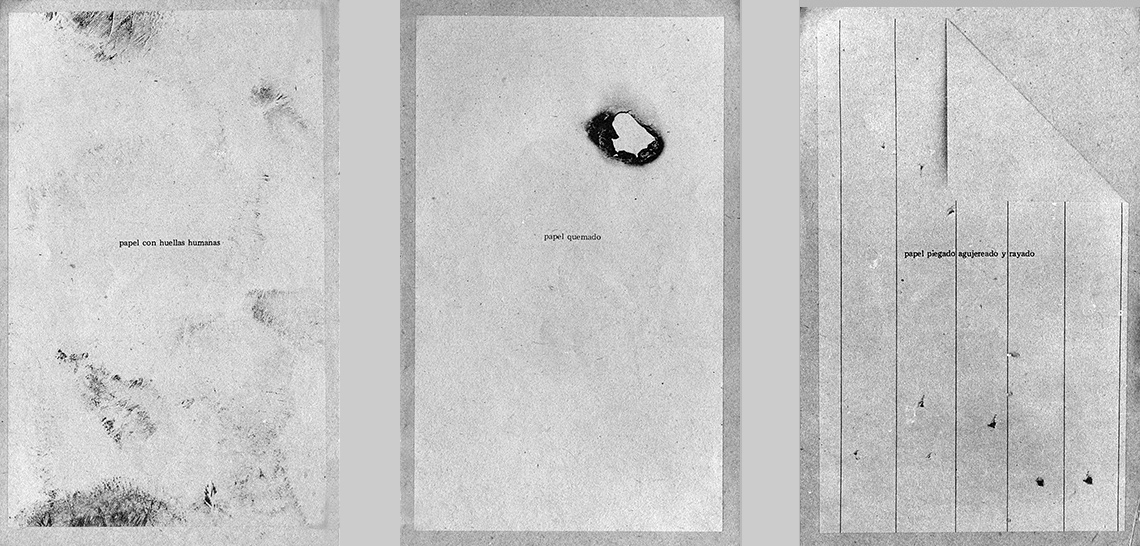

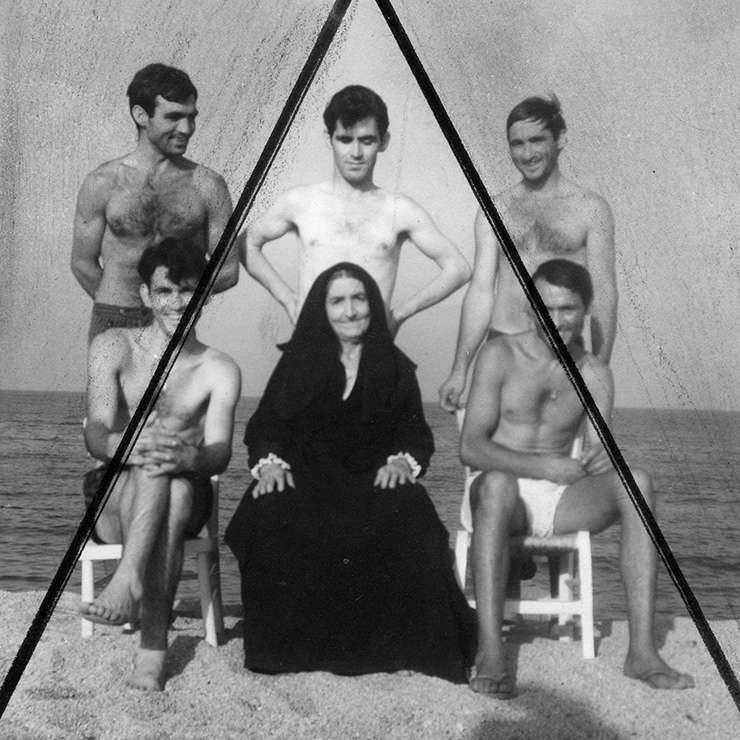

As is evident in El Cuerpo de Giulia-no, both novel and performance versions, Eielson created complex images and situations in which he explored the postcolonial marks on his place of origin. He used those marks to construct mobile and multiple cultural and gender identities. His practice as a whole is characterized by “exploration of the vast terrain between visuality, orality, and writing, which entails as well exploration of time and space.” [4] His production encompassed not only the visual and literary arts, but other hard-to-categorize works, works that move fluidly between disciplines and formats: sound experiences and poetic actions with, as critic Juan Acha put it, [5] “imaginary content” produced for both the public and the strictly private space.

In Eielson’s practice, time for creation is cyclical, and the work open, multiple, and simultaneous. Though his work with quipus has received more attention from collectors in recent years and his literary work is widely recognized—as an artist and as a poet, he is a cult figure for many—Eielson is still largely overlooked in accounts of Latin American art from the second half of the twentieth century, especially his non-object art and most experimental production. His inaugural presence in a program like La historia como rumor [History as Rumor] is, in a sense, at attempt to remedy that absence and introduce him to the general public as the total artist he was.

[1] Julio Ramón Ribeyro, “Eielson y 'El cuerpo de Giulia-no'” in Luis Rebaza Soraluz (ed.), Ceremonia comentada (1946-2005). Textos sobre arte, esté- tica y cultura. Lima, Fondo Editorial del Congreso del Perú, Museo de Arte de Lima, Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, 2010, p. 122.

[2] Even one of his first sculptures, La puerta de la noche [Gateway to the Night, 1948], makes a twofold reference, first to the architectonic forms of Tiahuanaco culture, and second to the work of the Uruguayan artist mentioned in the text.

[3] This exploration of the pre-Columbian imaginary pervades his work, albeit in different forms, over time. Arguably the most explicit references to it emerged in the nineteen-eighties in his self-portraits and pictorial series like en Ceremonias [Ceremonies] and Danzas rituales [Ritual Dances], tied to the Chancay culture, and Constelaciones [Constellations] and Cabezas de chamán [Shaman Heads], inspired by Chavín art. In those works, Eielson’s vision of the past evidences an interest in the temporal backs and forths of identity and in the figure of the shaman—and interest he shared with German artist Joseph Beuys. These works are poetically connected to his interest in science, rituals, and the cosmos.

[4] Letter from Eielson to Szeemann, June 1989. Harald Szeemann archive, Getty Research Institute.

[5] Juan Acha, Nudos. Jorge Eielson, artista peruano. Mexico City, Museo de Arte Moderno, Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, 1979.