Each man eating pieces of the island…

mist covering the scandal of the savannah with its icy disguise,

each palm proudly cascading in a green jet of water…

—The Whole Island. Virgilio Piñera

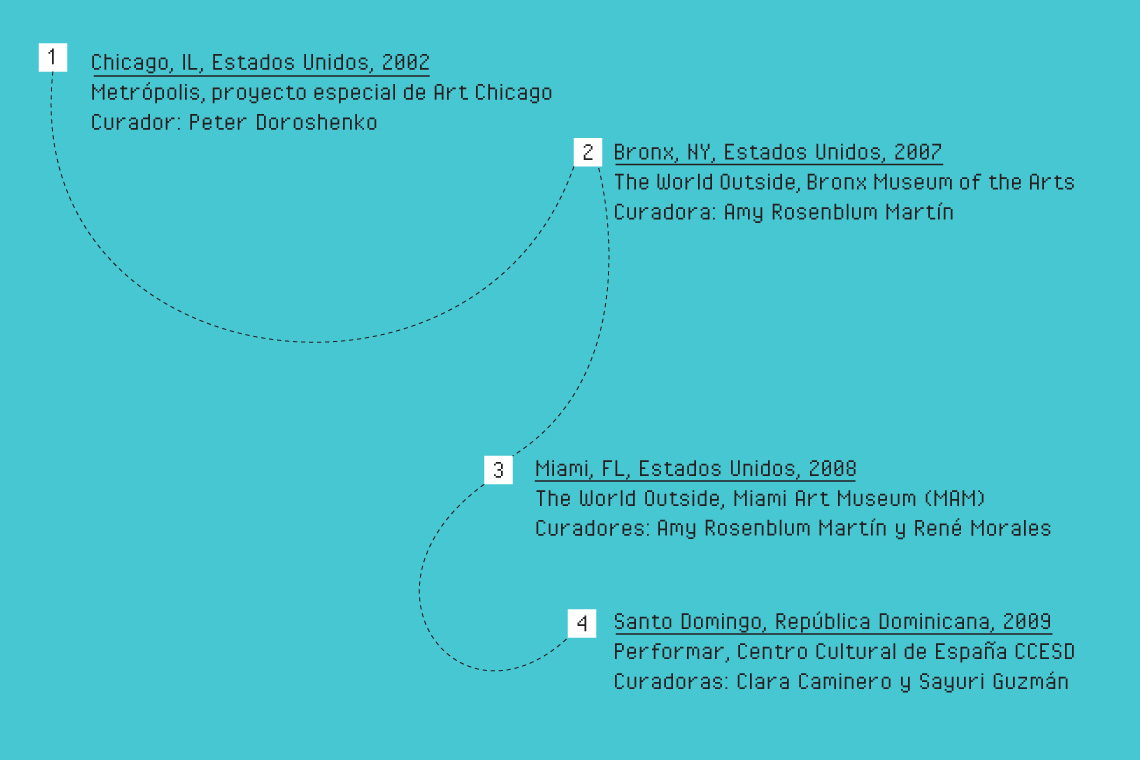

Quisqueya Henríquez is an artist with roots split between two islands. She was born in Havana and she grew up in Santo Domingo; she studied in Havana and she produced her work in Santo Domingo. Her production is extremely important to Caribbean art. Her pioneering work addresses critical issues that had largely gone unengaged in the local and regional scenes, among them the duality and bipolarity of islands and archipelagos; isolation and sound boxes; stereotypes and local types; migrant subjects and rooted subjects. Quisqueya uses a range of languages to discuss islandness. She reflects critically on the construction of fictions from spaces of power. She makes work that openly questions nationalisms. On the basis of the archetypical scenes she invents, she engages, and even questions, the ambiguity and antagonisms of current aesthetic logics. Her practice is rife with proposals that, from outlying territories, refer to discontinuity.

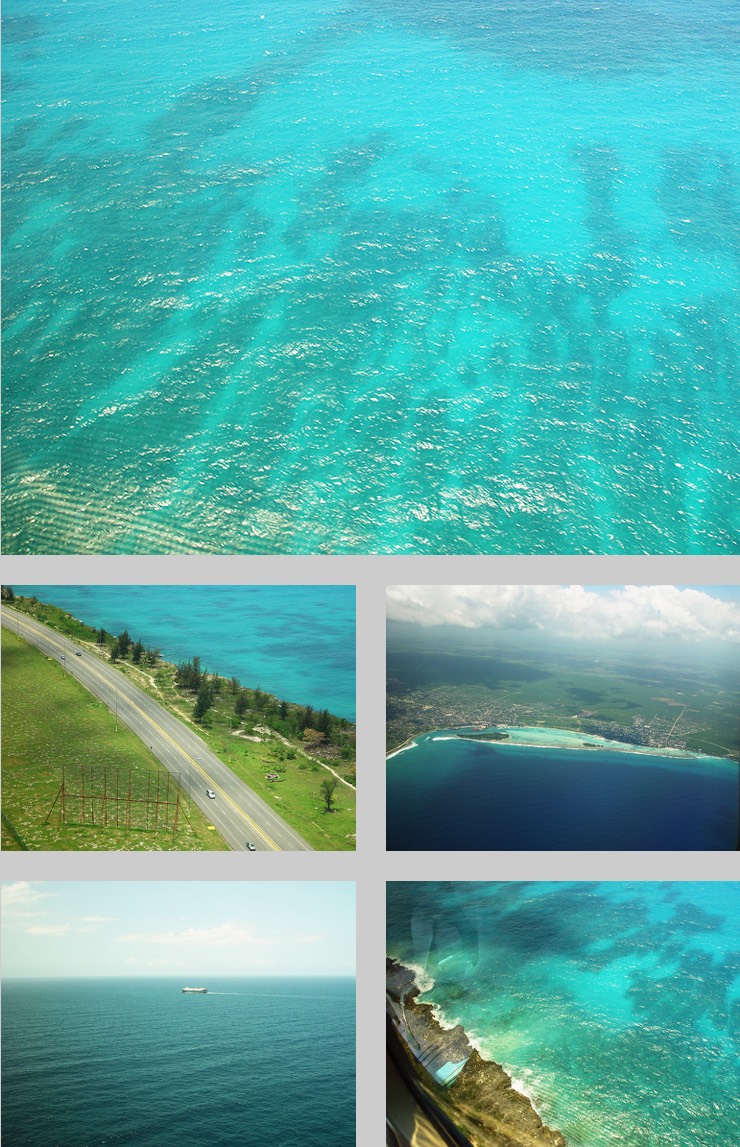

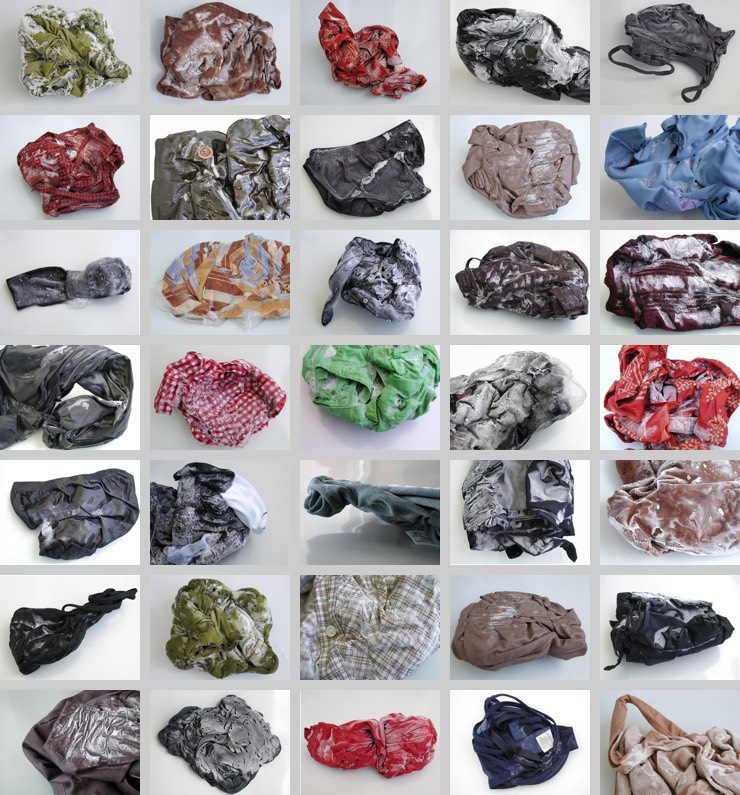

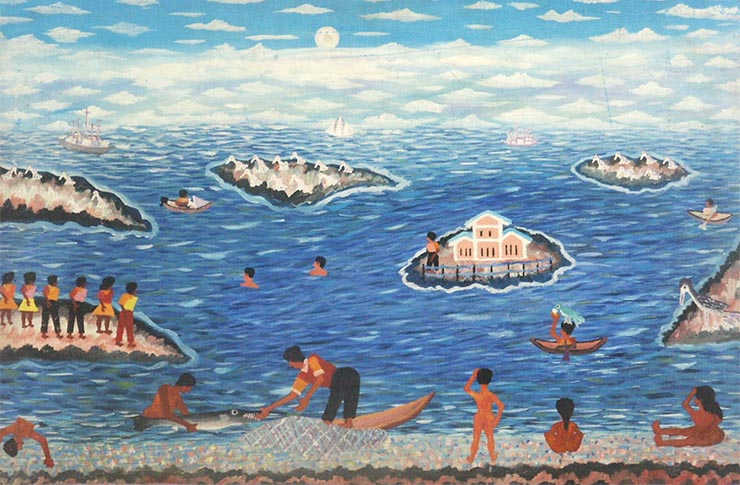

When she returned to the Dominican Republic at the end of the twentieth century, she worked on the Burlas series, a body of works that revolves around narratives of the tropics, mostly the Caribbean. The works address the stereotypes constructed in relation to the sea and islandness. But her art does not deal with just any sea. At the risk of seeming idealistic, I must clarify that the sea in her work—and the sea I am thinking of here—is exquisite and uncanny. Nor does Quisqueya refer to just any island. She addresses, rather, those emerging pieces of earth and their meaning as they bind and release her in turn. In the intimate relationship to islandness reintepreted in Burlas, then, strands of utopia exist alongside moments of violence. The utopianism lies in the formulation of impossible possibilities, not in resistance to the substratum of violence. The series is also highly autobiographical. It is a sort of logbook of her return, and everything it meant, the bitter and the sweet. In Ropa congelada [Frozen Clothes], a key piece in the Burla series, Quisqueya freezes every garment she owns in industrial freezers. Her daily life is frozen, subject to a radical thermic variation and anoxia that not only reshapes it in time, but also bares it of memory, scent, presences. The uncanny—that form of fright that affects things known and familiar—takes hold in pieces like Sangre congelada [Frozen Blood]. Blood, in all its scandal, undergoes sudden changes in temperature until it is solidified. In this bloodletting, consistency is the enigma. What does the blood tell us? What is in it?

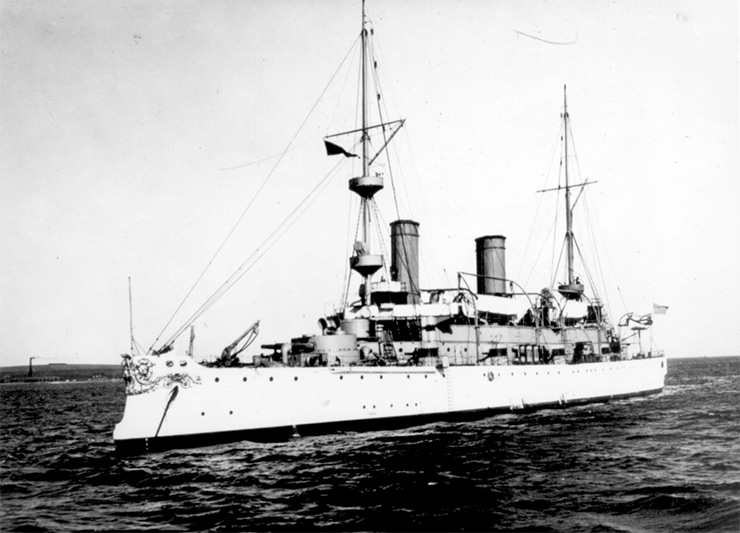

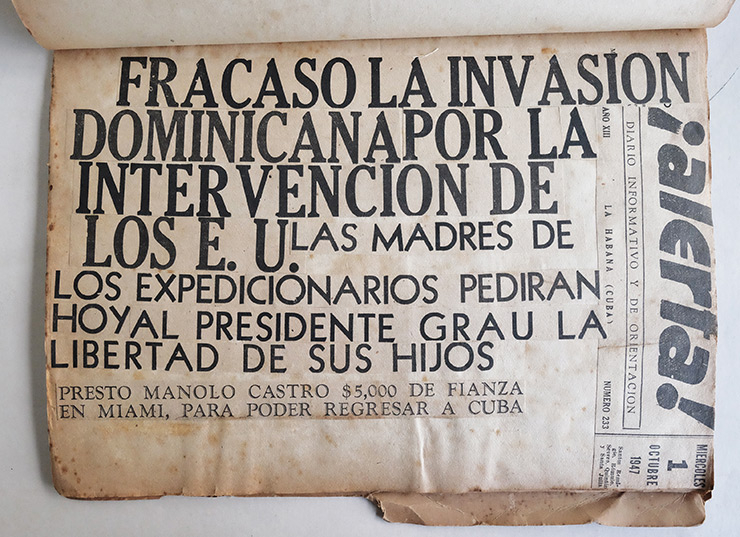

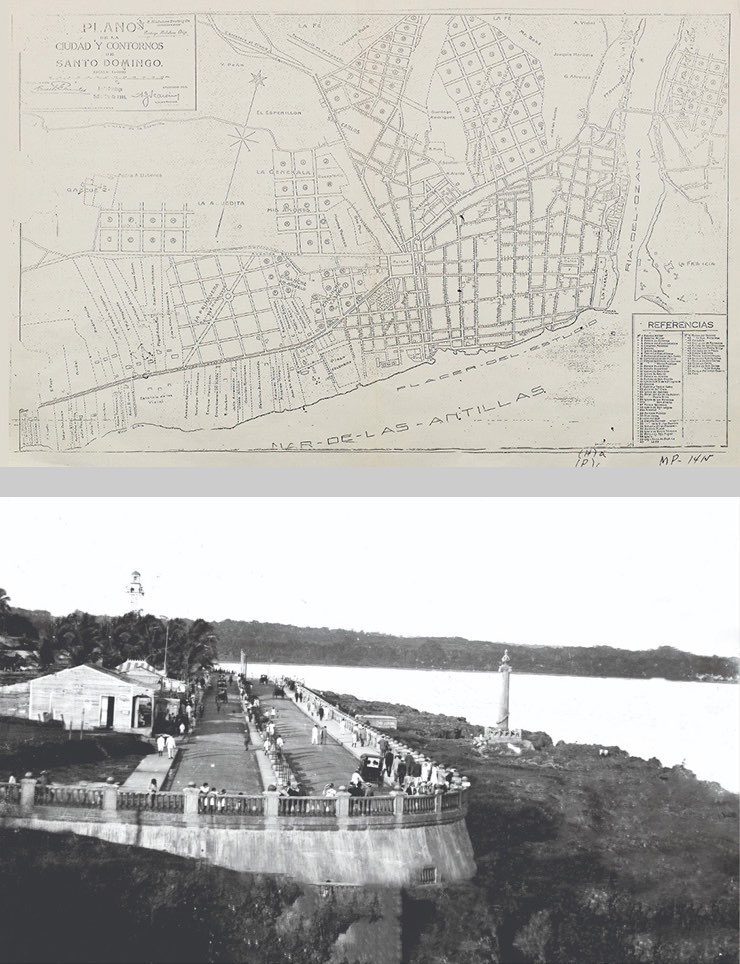

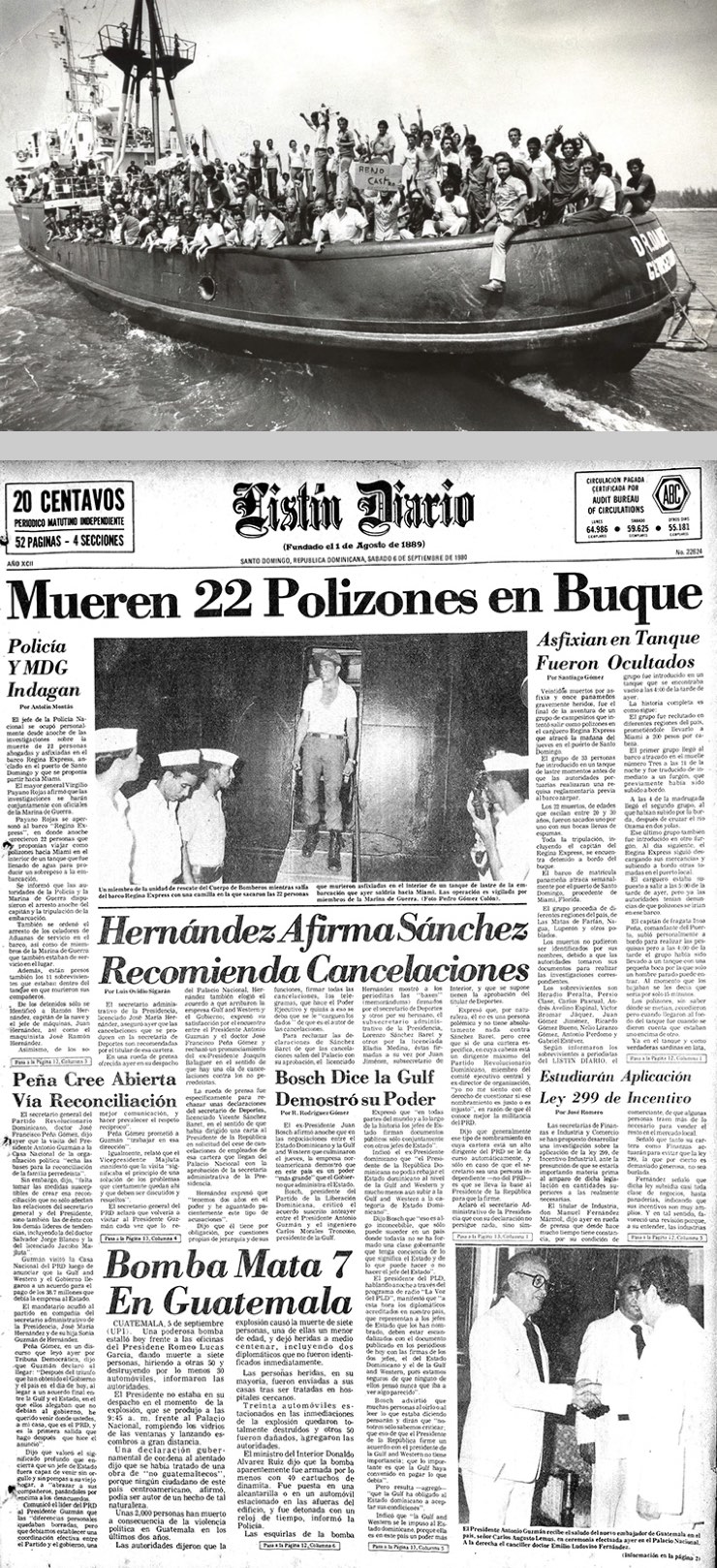

Burlas recodifies and disassembles notions like temperature and the ephemeral. And that takes us to the story of the ice cream. Thanks to Quisqueya’s ability to alter established orders and throw off perceptive norms, ice cream—an ordinary object to be savored and desired—becomes, in her work, an instrument to question learned histories. Helado de agua de mar Caribe [Caribbean Seawater Ice Cream] asks questions personal and autobiographical, as well as historical and social, to name just a few. Key to making this ice cream a weapon is Cuban poet Virgilio Piñera’s The Whole Island and its “curse of being completely surrounded by water”—a phrase at the top of the artist’s mind when she was making the work. While it is true that that “curse” determines much about the ice cream’s configuration and poetics, both to its favor and its detriment, what Quisqueya is able to capture in her construction are incongruences and silences. This ice cream’s argument lies in the gaps between the Sargasso Sea and the Mona Passage. The act of conceiving, producing, and sharing the seawater ice cream is also the act of handing out—to those of us eager to take them—her doubts and certainties, and references to that fluid body. And among those eagerly shared notions is the understanding of the sea as source of histories. Its oft-cited characteristics—fluidity, endless movement, and changeability—are offset in this action by the idea of retreat, exclusion, and isolation.

I have lived with and tasted a number of versions of this ice cream. One of the photographs yielded by the action has been in the Centro León’s permanent collection since the work was awarded at the Concurso de Arte Eduardo León Jimenes. Thousands of people have walked before that image. Over the years, I have heard so many readings and accounts of it—and I have constructed my own, some of which have even earned Quisqueya’s approval. The one I have told here is only one of them.