New York. March 2002. I find sand in the bed where, at my sister’s generous invitation, I sleep in her apartment in Manhattan, and I have a vision that the dune in Lima has been through here. I realize that there are always dunes walking around the world, dragged by our feet from one place to another. I think of the pebbles that Francis Alÿs registered in his shoe after taking a walk around London in 1999:

Pebble Walk

A walk from the northwest end of Hyde Park to the southeast end of Kensington Gardens, from 12.25 pm till 1.35 pm concluded with 7 stones in my right shoe and 3 stones in my left shoe. (Francis Alÿs, 15 April 1999)

All the remains we carry around with our steps are a basic part of a much broader phenomenon: they are fragments of a constant and endless geological nomadism. The action at the dune in Lima must be a poetic enlargement of an experience/trifle like that walk and those pebbles.

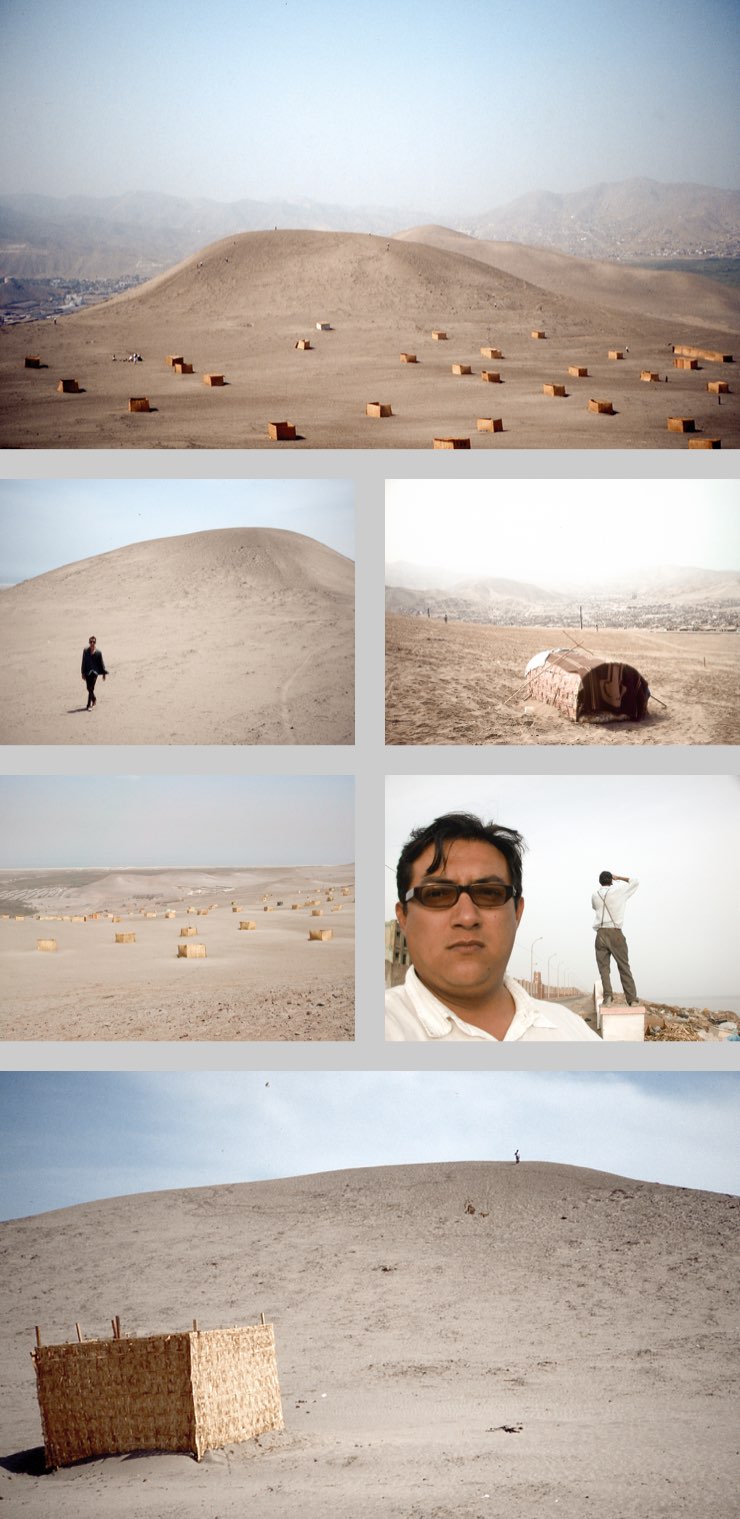

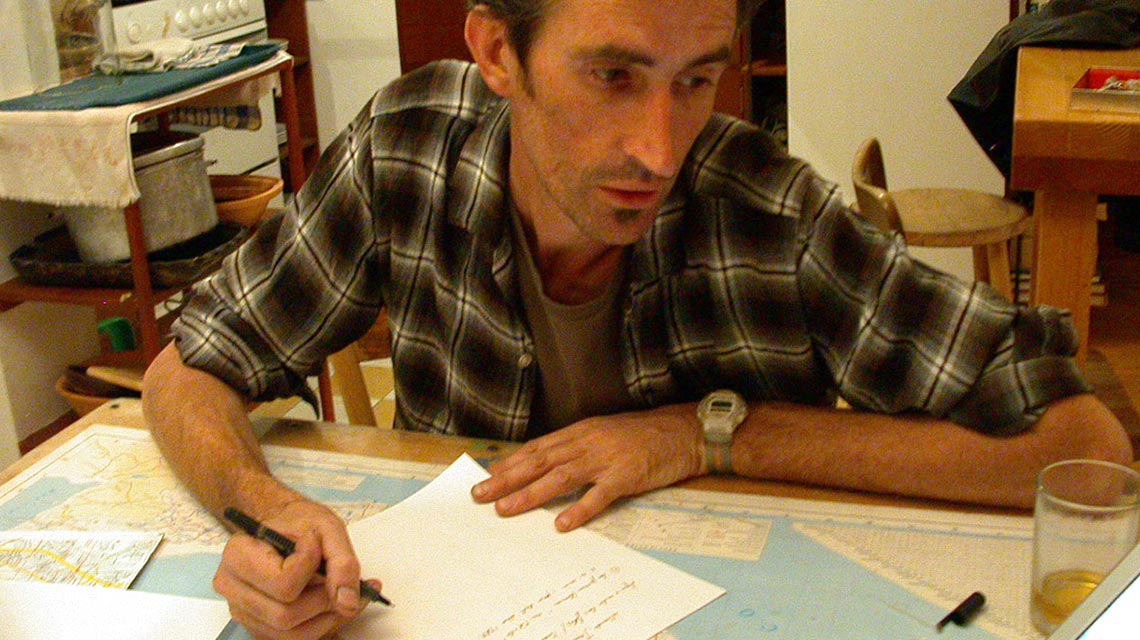

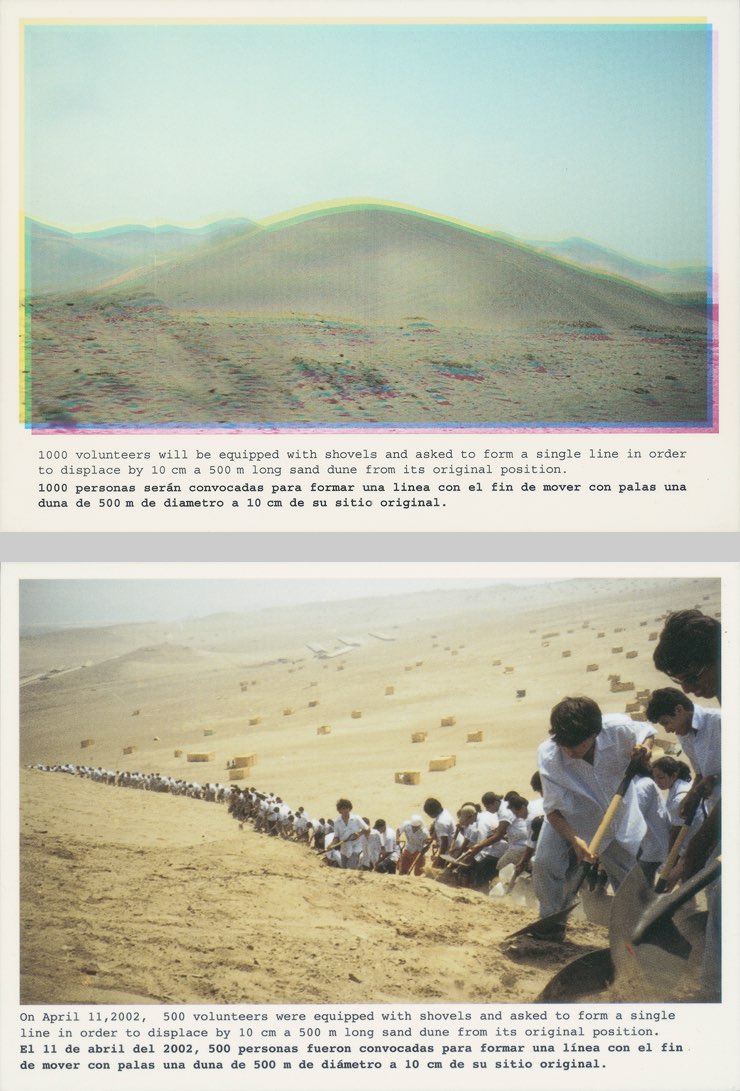

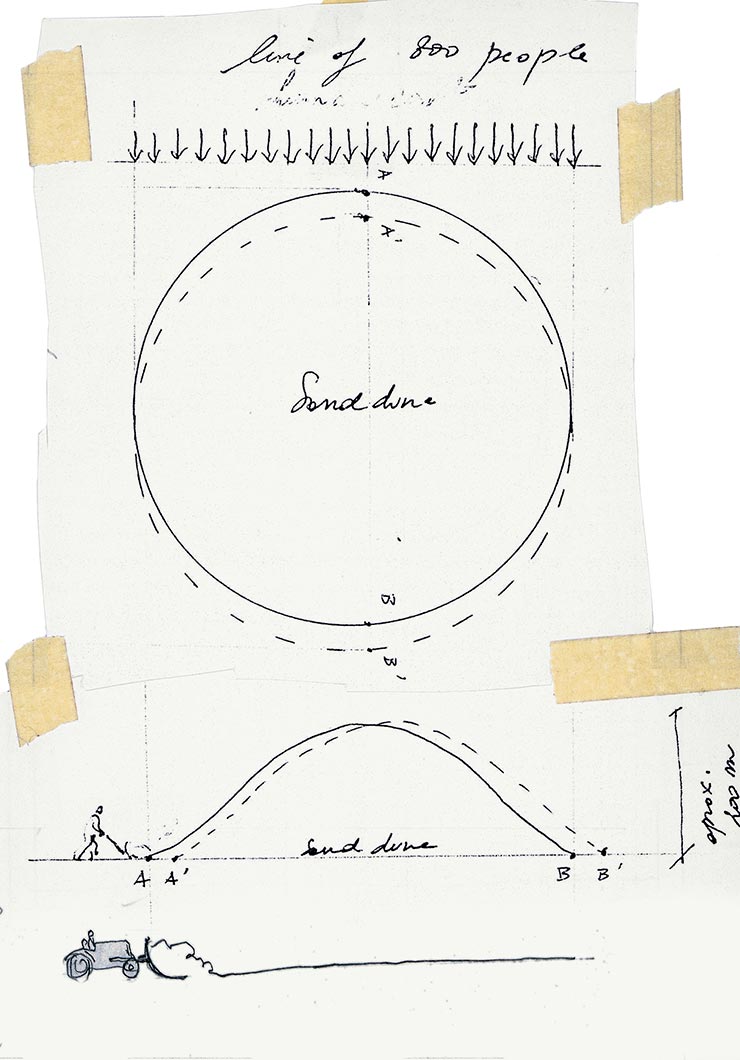

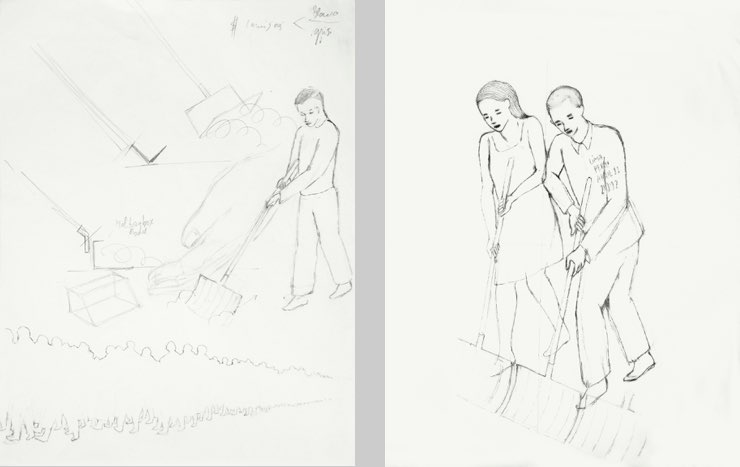

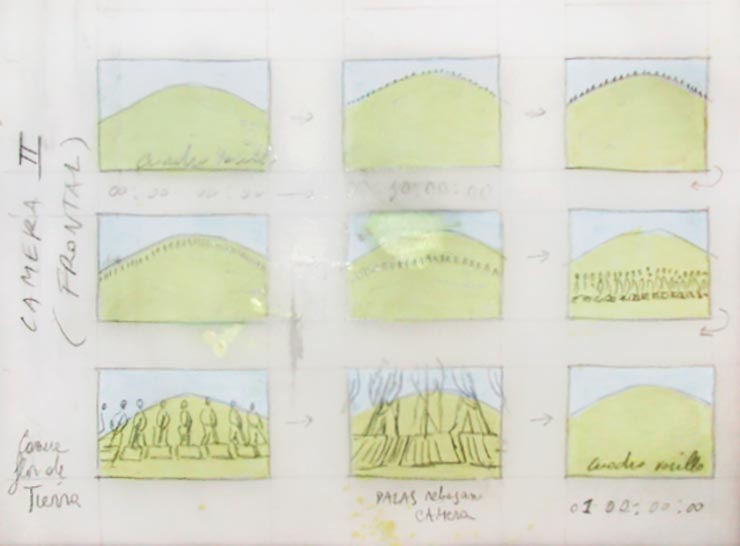

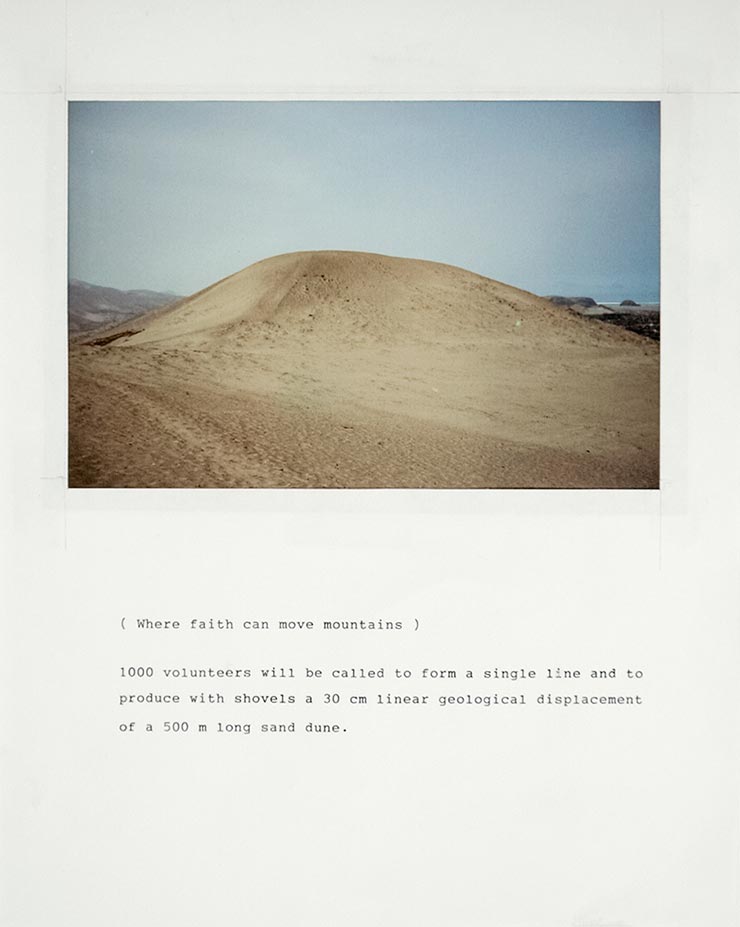

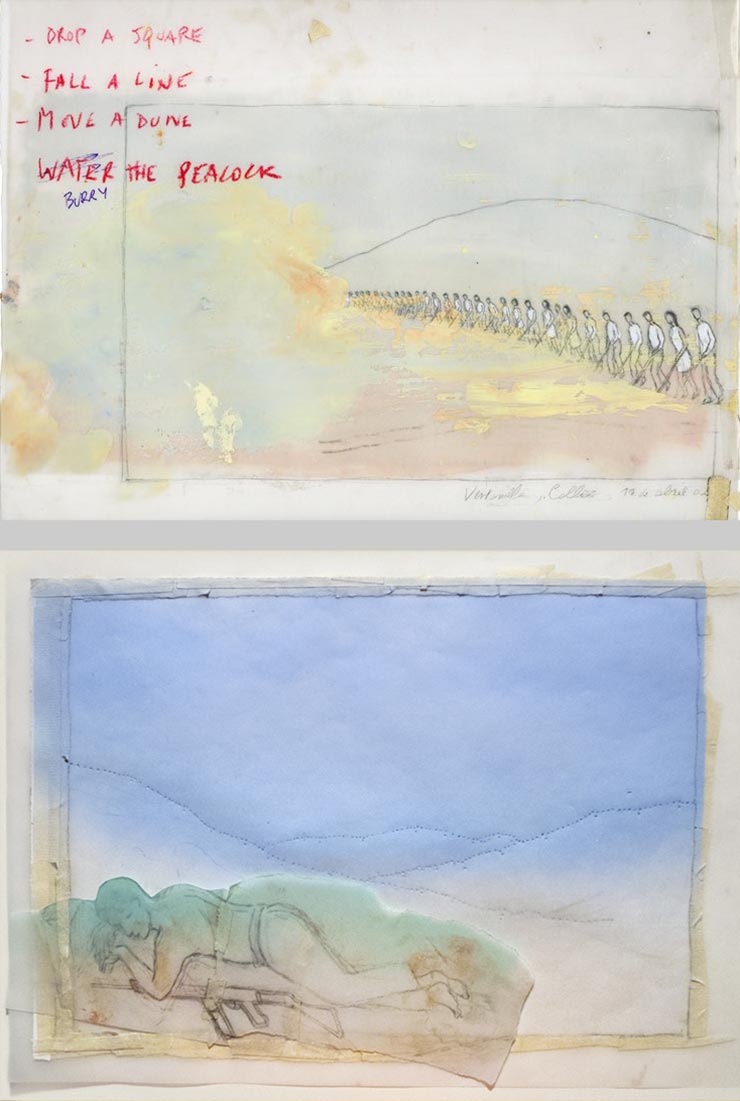

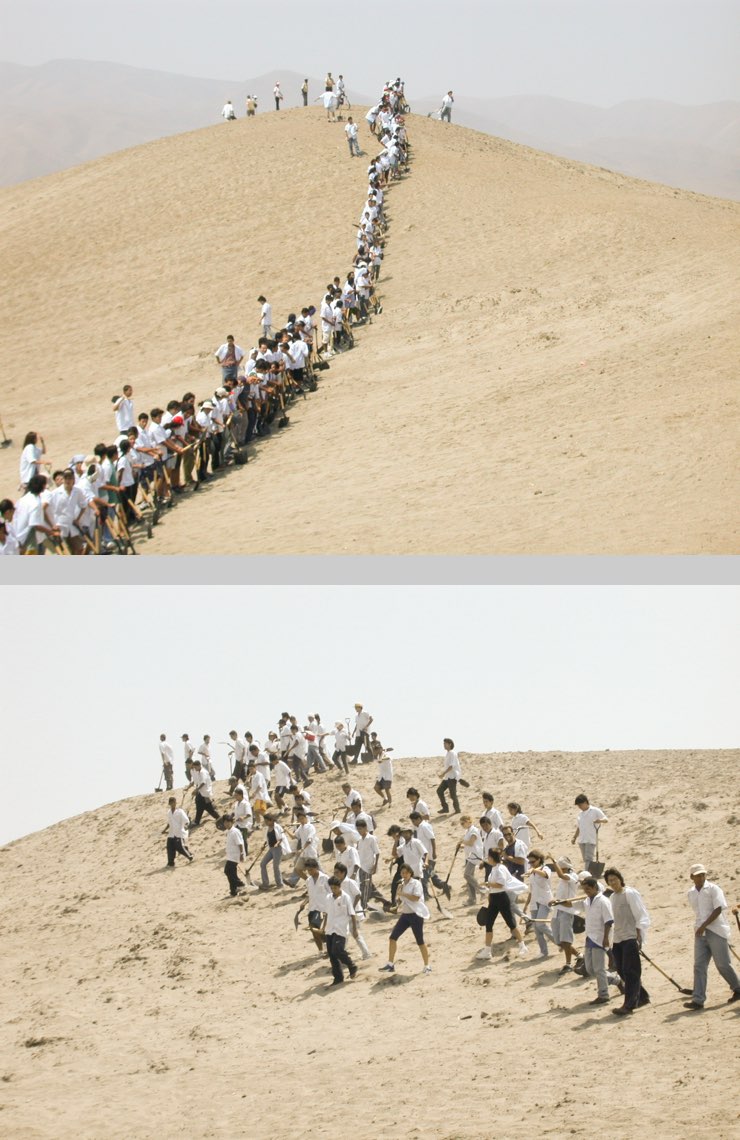

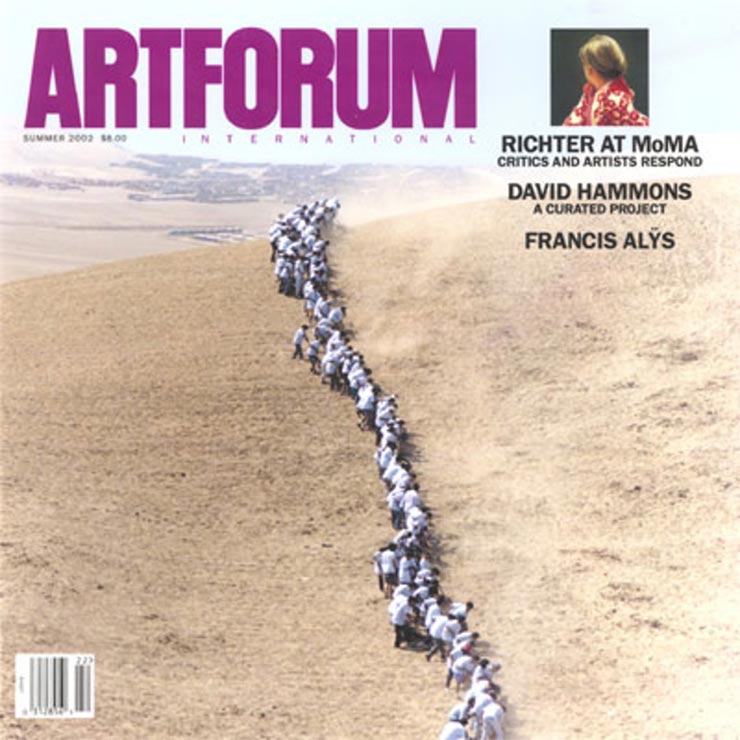

The facts. On April 11, 2002, the artist gathered five hundred people to form a row that, with the help of shovels, moved a dune measuring some four hundred meters in diameter on the outskirts of Lima.

How much the dune was moved does not matter. Let’s just say it was moved as much as necessary.

Projects. Four days after Alÿs’s action in Ventanilla right outside Lima, Peru, I met up with Richard Perales, the president of the Architecture Students’ Union at the National University of Engineering in Peru. I asked him a question that I, personally, would have found terrifying. “And what now?”

Richard was unfazed. “We have a number of projects looking forward: drinking the Atlantic Ocean, painting the sky blue, perforating the Andes.”

Lima, Peru. October 2000. At the exact time the awards ceremony for the Bienal Nacional de Lima, which selects the local artists who will participate in the 2002 edition of the event, was taking place, there were clashes between police and protesters (students and workers) in Lima’s Plaza Mayor. While hackneyed speeches were being given and checks handed out to finance the production of the works selected, tear gas was being fired. What role can art play in those uprisings?

That morning, Francis Alÿs had gone to Ventanilla. He told me, with startling clarity, “A desperate situation calls for an absurd response.”

Biennial Epidemic. Lima, Tuesday, April 9. While waiting for the elevator at the Hotel Maury, Javier Tellez points out to Francis that there is a paradox in everything we are doing. Francis had sent to the Venice Biennale the previous year a peacock, the “Ambassador Mr. Peacock,” which wandered through the Biennale’s grounds in a gesture of indifference to the vanity fair of art biennials the world over.

With undying irony, Téllez says, “and you come to Lima with this whole circus … I don’t get it.” As if he himself were not doing something very much the same!

In fact, our presence at the Lima Biennial had to do with, among other things, a policy of absurd reciprocity: overblown investment in a territory and event apparently minor on the global art circle is more than an act of generosity. All of us who were there know, more or less consciously, that our participation in the Lima event was rooted in a call for solidarity. I am speaking, of course, of the fact that the Lima Biennial grew out of a symbolic coalition of resistance to Fujimorism.

For some of us, the invitation to the biennial came with an fortunate extortion: critic Gustavo Buntinx, who was involved in the Lava-bandera project of the Sociedad Civil collective, informed us that “the struggle against the dictatorship has brought together a wide front encompassing formerly divided factions of Peruvian culture and art.” Furthermore, the biennial was planning to take back Lima’s historic district for the people. It was never just a project, but a way to insert ourselves in a territory of political-symbolic negotiations on the place of art at a determined historical juncture.

Like earlier biennials in Havana and Johannesburg, this one in Lima used its context of crisis as launch fuel. The energy we witness today, even after the fall of Fujimorism, is part and parcel of a method some peripheries use to get a ticket into global art. The only way to keep our visit from turning into “cheap holiday in someone else’s misery” is for the biennial to provide local art with a healthy opportunism, a pathway from the visibility to the radicalization of the local.

The work of Fernando Bryce or of Giuliana Migliori, to cite just two examples, attests to the aptness of that formula. Any rise to fame for an artist from the global South depends on a certain dialectic between domestic tension and a foreign nod. The experiences of Johannesburg and Havana also act as warnings of the perils that operations of that sort hold. If local political and cultural elites don’t understand the possibility for dialogue and engagement offered by contemporary art, they may well let that ticket go to waste once the crisis’s political pressure seems to have lifted.

As a Mexican, as a half Peruvian, I think I have the right to cross the line of friendly criticism, at least slightly, and level a concise frontal critique. Given the energy invested by so many participating artists, the Lima Biennial’s decision to pay tribute to José Luis Cuevas (one of the countless local shining lights found throughout Latin American art history) was not only a distraction from the biennial’s contemporary program or a step backwards. It showed that institutions in countries like Mexico and Peru have failed to grasp the opportunities their dramatic situations afford.

As problematic as it may be, the role of biennials is crystal clear: to show only astonishing—extremely astonishing—art, art fresh out of the oven. Say no to canned national art.

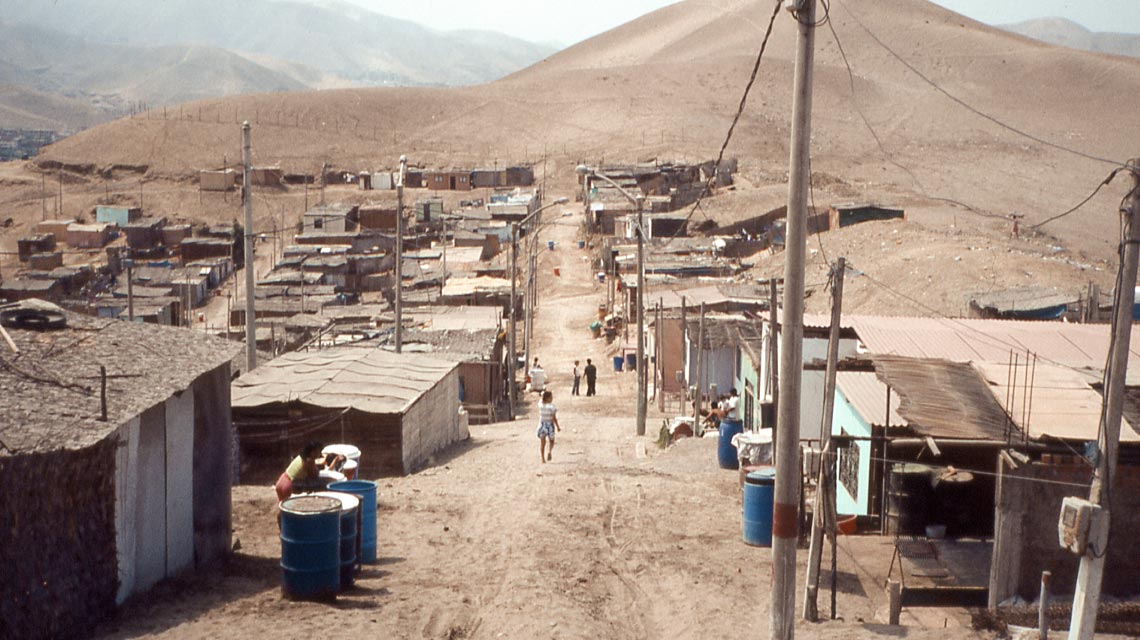

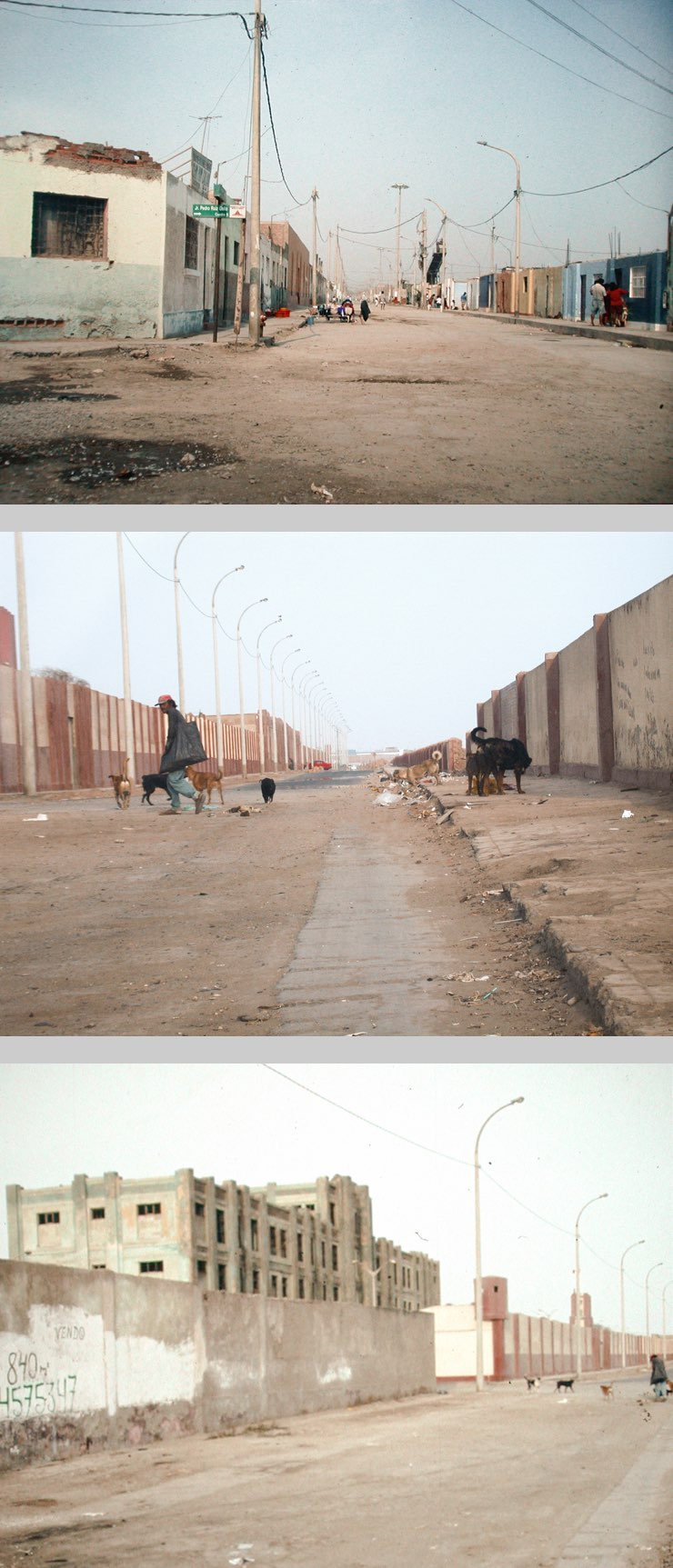

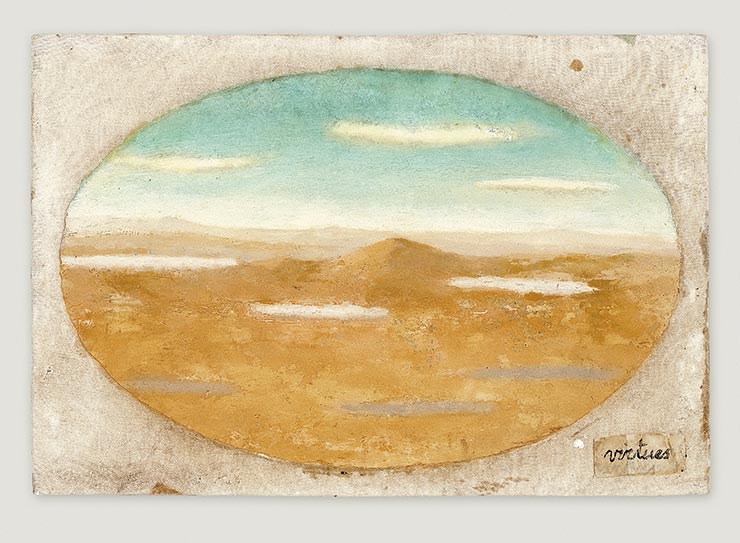

Migration waves: Lima has been moving its dunes for some time as it expands into a megalopolis and, through “cholization,” undergoes racial transformation. Migrants exert pressure on the terrain, causing the landscape to disappear by dint of urbanization. Obvious conclusion: any megalopolis banishes its landscape.

One of the main motivations for the project was to formulate a dialogue with how the absence of planning is what generates the urban layout in Latin America. Ventanilla is a prime example of what we might call vernacular urbanism: with their houses of reed, migrants demarcate streets where, sometime later, the authorities find themselves forced to create sewage services, supply water, lay electrical and phone lines, etc. No matter how dreadful the landscape of these young settlements may be, the “favelas” in Brazil and what we in Mexico call the “lost cities” are great concentrations of hope. These towns usually house the most daring members of their local communities, people who use vines, wood, or aluminum to erect formally and architectonically extraordinary structures. With savvy use of cubes, cylinders, paraboloids, and prisms, the architecture they build, no matter how provisional or rudimentary it may look, constitutes a sort of spontaneous functionalism.

The time has come for the inhabitants of cities to recognize the energy and creativity of those we have always considered “invaders.” In the absence of capital or policy, we are indebted to them for the dynamism of what we pretentiously call “our city.”

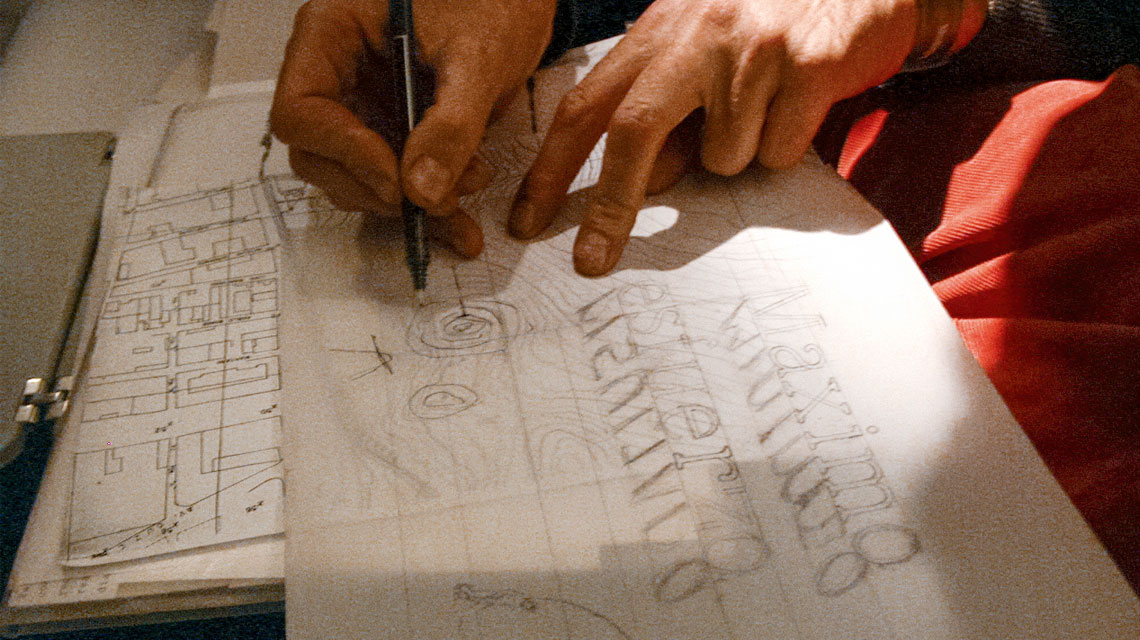

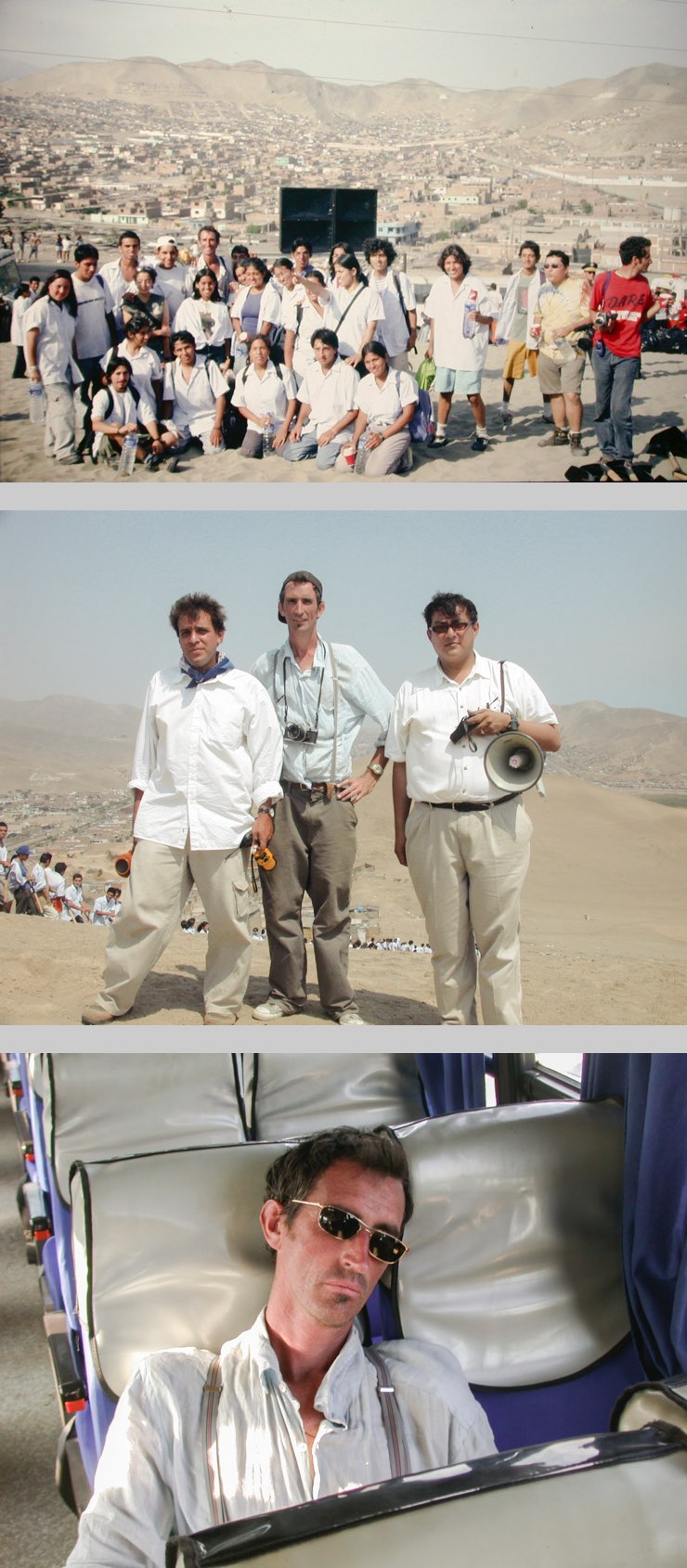

Dialogue with engineers: It was for a number of reasons that most of the participants in When Faith Moves Mountains were students at Peru’s National University of Engineering. Some were practical in nature (a high concentration of students, the fact that members of the Students’ Union took interest in the project, the support of the university administration), but one was conceptual. The action was, after all, a work of civil engineering: hundreds of shovel-bearing men and women altered a territory. Furthermore, the action allowed us to bring the architecture students face to face with the popular constructions in Ventanilla’s neighborhoods, which might turn into a source of inspiration and a challenge. Finally, it was a chance to interact with people who did not have a set notion of what art is and what it is not. The participants accepted the project’s challenge on the basis of its possible meaning, not out of a conviction about what constitutes “the contemporary.”

But, as a student at the university’s school of economics put it, the action also meant engaging students at a technical and scientific university in an irrational act. Spread faith in absurdity at an institution dedicated to calculation.

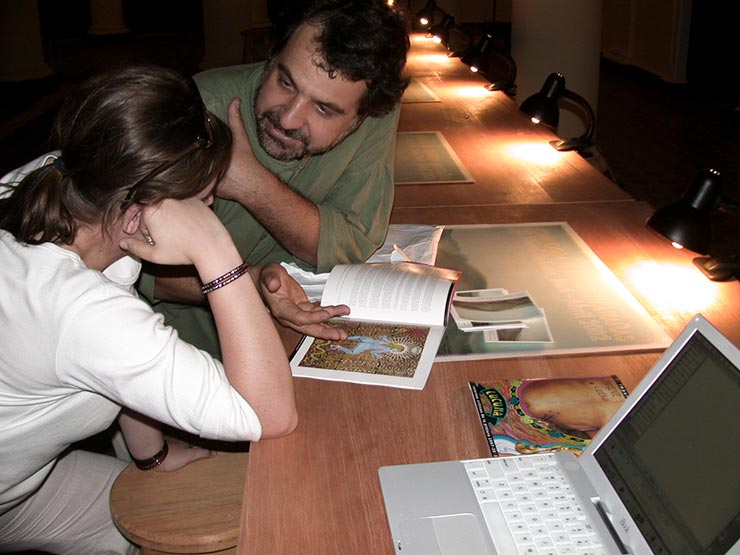

April 15, 2002. Drinking an Inca Kola at Cordano bar in Lima, I show a group of colleagues photos of the April 11 action. Artist Liliana Porter remarks that, pretentious though it may sound, Francis Alÿs is a poet of sorts: the work is a simple image that communicates without the mediation of a complex theoretical discourse. And I can’t help saying to Liliana that Francis is indeed a poet, but “this time his verses were extremely intricate. Gongoristic doesn’t even say it. Their meter was possessed by the devil."

Complaint Department. The sun on top of the dune was brutal. We had not anticipated that the sand would rise up in clouds and burn participants’ eyes. I still can’t understand why they didn’t give up. I do understand that their commitment was born of a combination of conviction and sense of destiny. We took pains to convey the action’s metaphors, but once the hundreds of participants were there in the desert, each and every one of us knew there was no turning back. Solidarity is strikingly fatalistic: you cannot give up for fear of disappointing someone else doing the same thing you are. You even know that to give up would be catastrophic—it would lead others to desert. That is the logic of a mob mentality.

For the organizers, though, the pleasure of seeing the action take place was never without a pang of guilt: people would shout for water from the dune every so often. But the camera kept rolling.

Chinese tales. In China—curator Man Ray Hsu tells me—it is considered a misfortune to have a mountain in front of your house. And from there the moral to a popular tale: Once upon a time there was a man obsessed by the sad fact that there was a mountain right outside his door. One day, determined to get rid of it, he started carrying the soil away in a pail. A neighbor, alarmed by the sight, warned him that he would never finish up the job. The man said, “Maybe so, but I will have a son, and he will have a son, and my son’s son will have a son….”

On Tuesday, April 16, a student at the National University of Engineering told me he had once seen a Chinese magazine from the Maoist period with photos of one of the miracles attributed to Chairman Mao, among them an entire town that had moved a mountain by hand in order to fill in a ravine.

San Isidro, Saturday, April 13, 2002. We visited Huaca Juliana—those pyramidal structures that pre-Incan cultures built on the Peruvian coast—where we stumbled upon a unexpected sight. The pre-Columbian mound had been fenced in, trapped between the building walls and houses built around it. Not only didn’t the Huaca have any space to walk around in, but it was suffocating to death. It is, actually, the yard in back of the water tank that feeds the neighborhood’s tubing. Like the Indians themselves, this Huaca has been closed off in a reservation. All that fencing makes it look downright dangerous.

Social delay. The idea of hope has a delay effect worth thinking about. Faith is a negotiation, a mechanism where you resign something in the present as an investment in an abstract future promise—the Catholic trap par excellence. Be that as it may, any look to the future, and hence any action, depends to some extent on delaying both satisfaction and effect. Let’s set faith free from the domain of theology.

Illusionism. Throughout the project, Francis Alÿs bore in mind that what we were going to do in Lima would be a sort of illusionism. Like Uri Geller, who had crowds rub teaspoons promising they would be able to bend them, we were heading to Lima to convince hundreds of people that they could work a miracle.

Yet, in that hypothetical dialogue with the terrain of gurus and prophets, we knew that the invitation was ultimately atheist and enlightenment. When a miracle is an organized collective act, it is diminished. Its miraculousness is reduced to the act of convincing, of generating commitment, on the part of a group, to carry out a task. Once the participants—shovels in hand and shirts on back—were lined up in front of the dune, that is, before they had moved even a single grain of sand, the miracle was complete. That fact that those people would actually move the dune fell into the terrain of the remarkable.

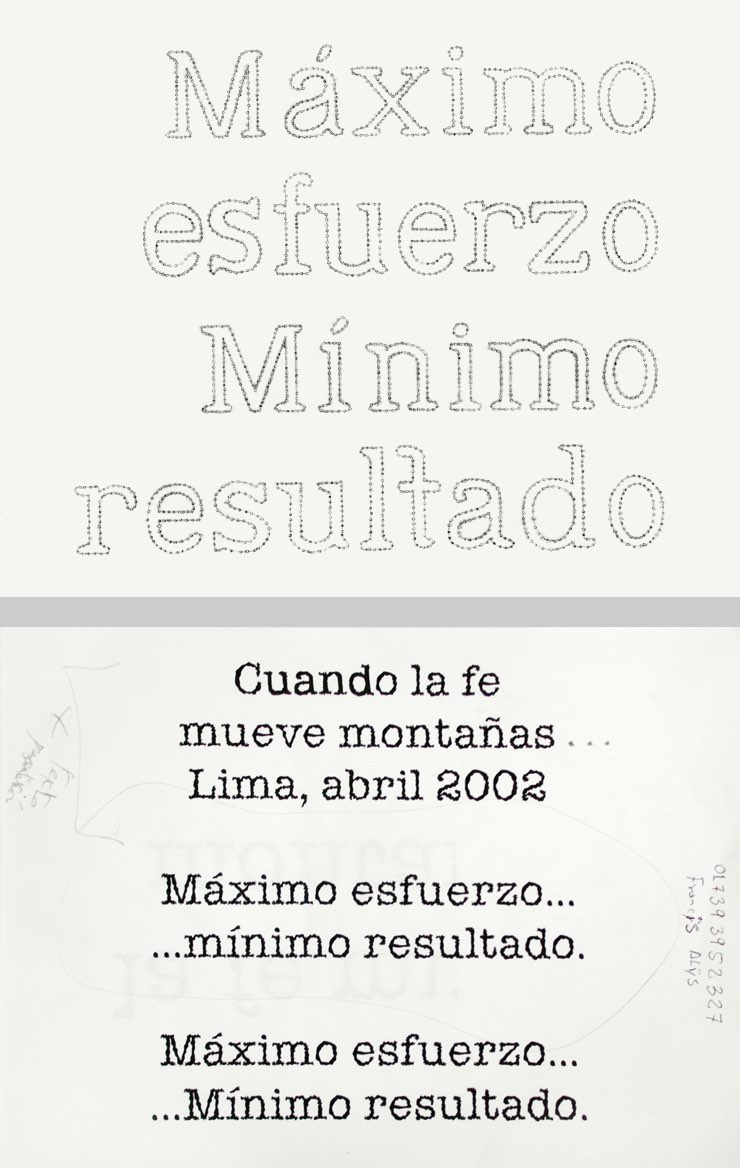

Maximum effort, minimum results. When Faith Moves Mountains is a patent application of the Latin American non-developmentalist principle. It is an extension of the logic of failure, programmatic dilapidation, resistance, entropy, and economic erosion. At play was formulating a parable of sluggish productivity that also showed, epically, the effect of minimal changes enacted through collective effort. It was not about formulating a principle of non-action: concentrating in a specific time and space the mechanisms of an economy that resists the dogmas of modernization, neoliberalism, and the arithmetic perversion of “efficiency.”

By evoking that economy we of course become, to some extent, abettors of the evils of underdevelopment. Oiticica put it clearly, “From adversity we live.” Other minds, minds clearer than ours, will be left the task of determining if that abetment is as cynical as the abetment of the evils of development.

Images against smell. Impossible to convey the atmosphere in Ventanilla, its mix of the scent of fishmeal factories swept in by the breeze and garbage rotting in plastic bags at each step. Nor can we convey the feeling of astonishment upon seeing, from above, the houses of the settlements, the factories, and the blue line of the sea.

Mass movement. Simulation of social mobilization or invitation to physical mobilization. At a juncture when politics is ceasing to be Newtonian politics (it dawns on us that every time we speak of the masses and power, we equate the social and the physical), Alÿs’s act makes reference to the fact that, in Latin America, many of our battles have not yet entered the realm of what Foucault called the microphysics of power. They are still waged around the old questions of property, government, social rights, housing, water, land. In Mexico and Peru, even today taking political action means mobilizing masses in the streets, that is, protesting, showing the public power the ghost of rebellion. There are, however, reasons to believe that a crisis is imminent for this age of mass politics. The democratic change in Mexico in the year 2000 was largely indebted to telemarketing. In Peru, Alberto Fujimori fell not only because of social movements, but also the havoc wrecked by video.

Remote curating. Not being totally in control of the project, no choice but to perform the work of an “agent” or a “diplomat.” While working with institutions in the global North means disregarding practical concerns and concentrating only on conceptual questions, working with institutions in places like Lima or Mexico is in and of itself an act of faith. There are thousands of reasons this project could have failed. But, like gambling addicts, we just upped the stakes after each setback.

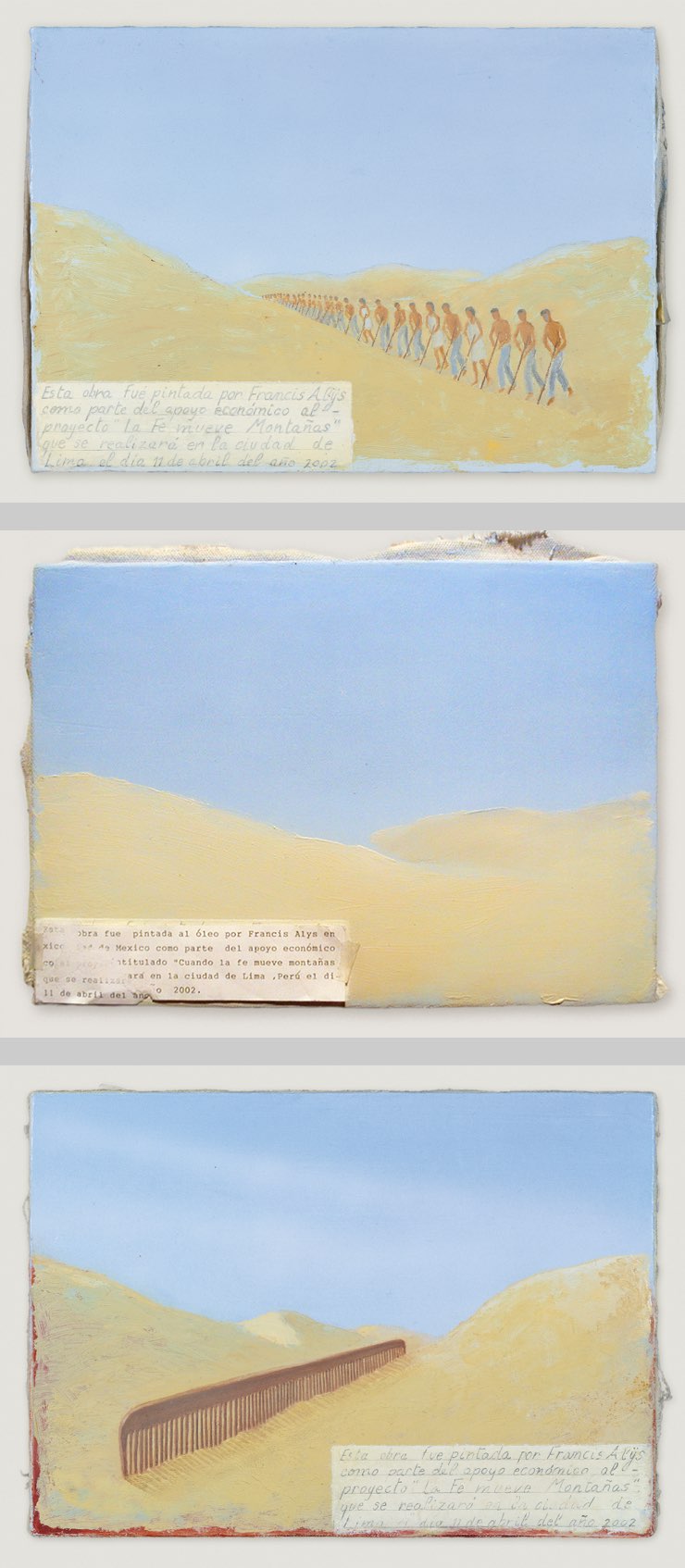

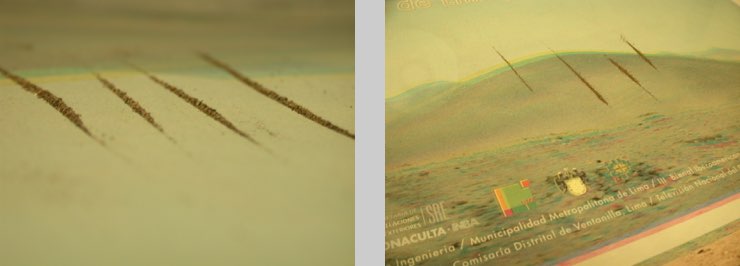

Relics. Any miracle requires physical proof. Moving a dune should not leave a trace.

At most, it combs the terrain. Francis Alÿs often imagined the multitude pushing the dune like an enormous comb where each worker is one of its teeth. Indeed, at the end of the act the dune was streaked as if a huge comb had swept over it. Those lines would soon be blown away by the wind and new constructions. The last thing we wanted to do was be another stop on the global South’s tourist circuit.

Land art for the landless. Land art has always been suspected of romanticism. It turns its back on the city, whether because it formulates an imaginary return to the Stone Age or to the works of so-called great civilizations, or simply because it entails an almost metaphysical relationship with the landscape. Like the Nazca Lines, Walter de Maria’s Lightning Field and Douglas Huebler’s trenches were dialogues with an absent god located far from any audience without the interference of modernization. Sculpture was banished to the desert to dodge the unfaithful competition of the city that, under capitalism, reinvents itself every second.

The dune action resocializes land art: it turns sculpture into an experience of the masses or, rather, into a relationship with those who search for land.

April 11, 2002. In the bus back to Lima. “So far, we have been a scam. From this moment on, all we will do is lie.”

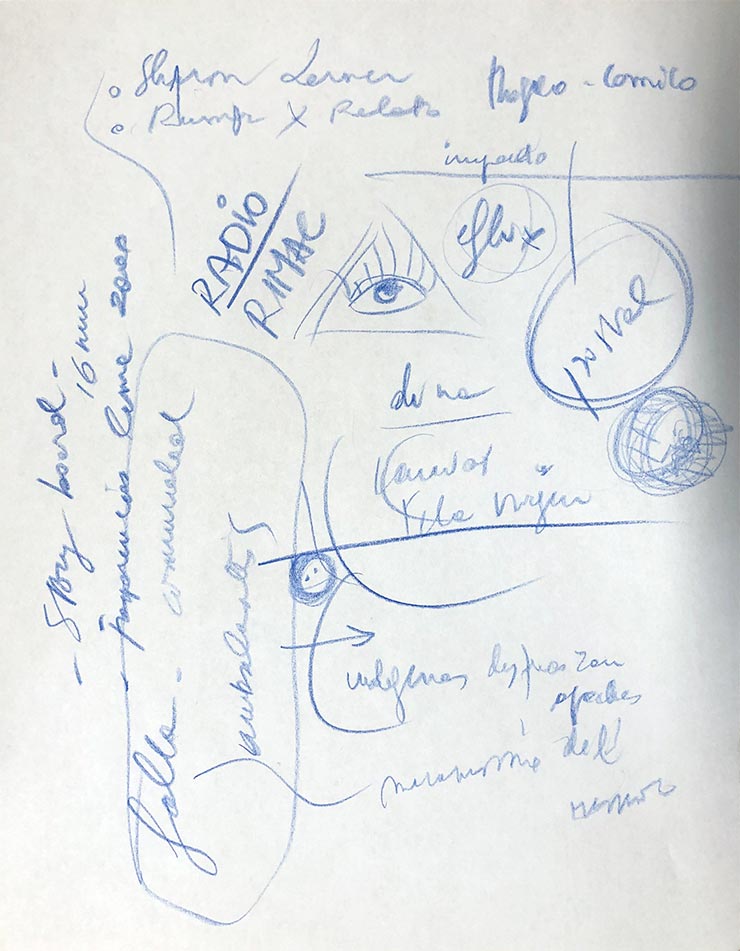

Literature. Critics often associate Francis Alÿs’s art with literature. Many have attempted to find a connection between his actions and Borges or Kafka—and, in fact, Alÿs’s walks set out to be, first and foremost, fables, action/fictions. But it is mistaken to think that the anecdotal or the legendary always already takes us to the writer’s desk. It is not a question of making a literary work, but of going one step further back to the invention of an urban myth. Unlike literature, the real story is changed by each speaker who spreads it as rumor.

Before the Romantics captured folk tales in books, before the Brothers Grimm or Andersen, before Riva Palacio or Fernando Palma, events were recounted by word of mouth; they were always open to the narrator’s invention and fancy. The purpose of moving a mountain in Lima in April of the year 2002 was not for someone to write a definitive or perfect text. On the contrary, the artist set out to nourish the local imaginary, just like the circuit of anecdotes that, in a favorable light, is the realm of “neo-conceptualism” in the circle of artistic information.

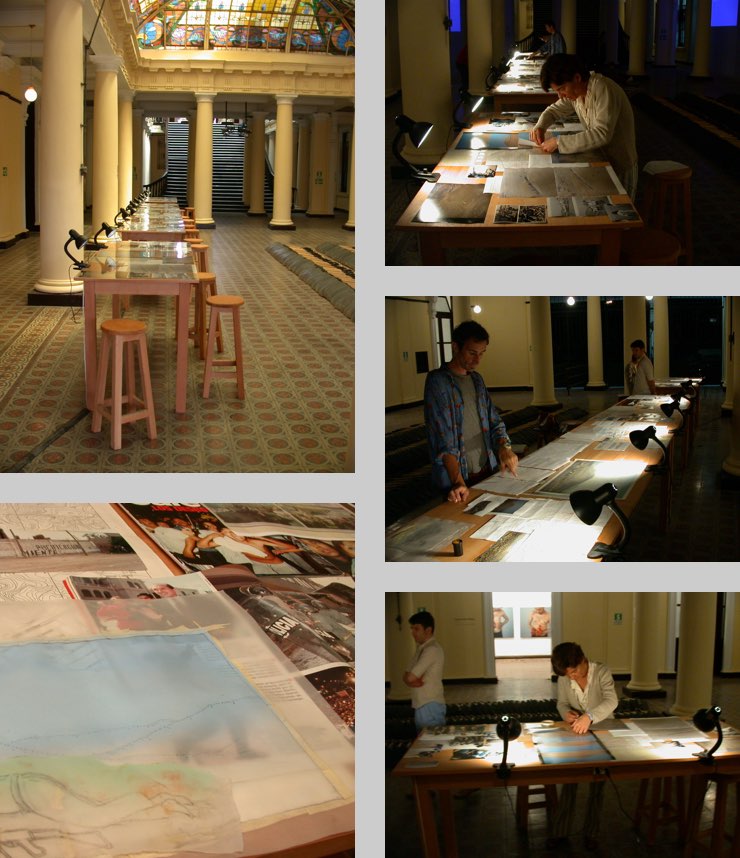

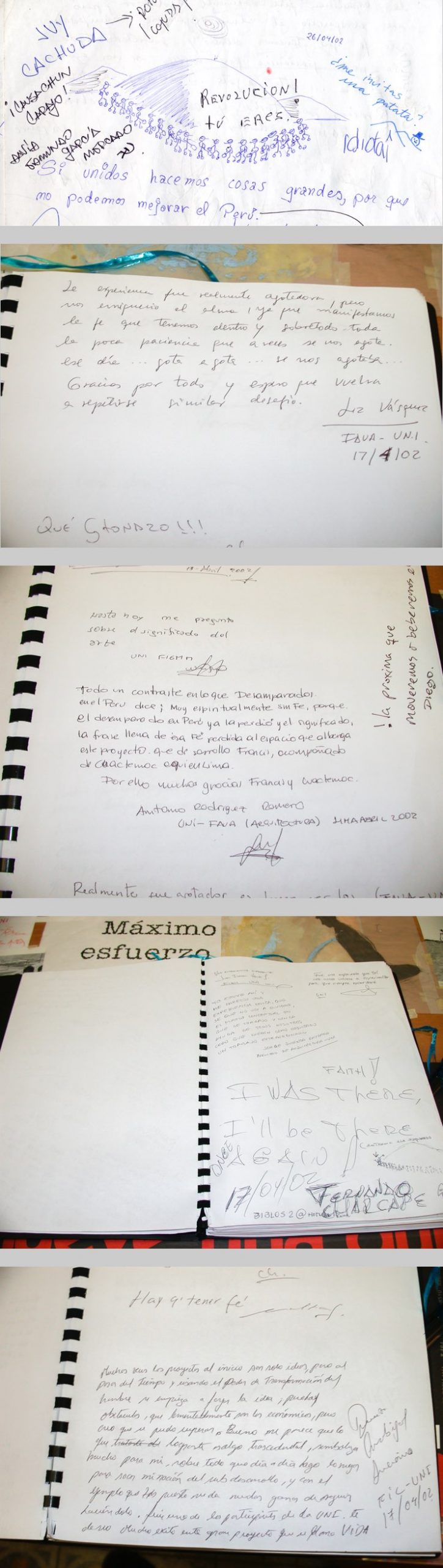

Actually, each one of the hundreds of participants in the action are the authors of the story: insofar they went home and recounted what they had done, they saw to reinventing the memory of what went on and its associations. The work’s installation in an exhibition venue is just one more of the apparitions of this market of multiple voices: the viewer is not offered just an image, but also documents that attest to an event destined to be disclosed as, in verbal form, it makes its way back to the city that produced it. In an age of image proliferation, the action at the dune set out to multiple narrators—and that was its real political effect: to restore, momentarily, an oral community.